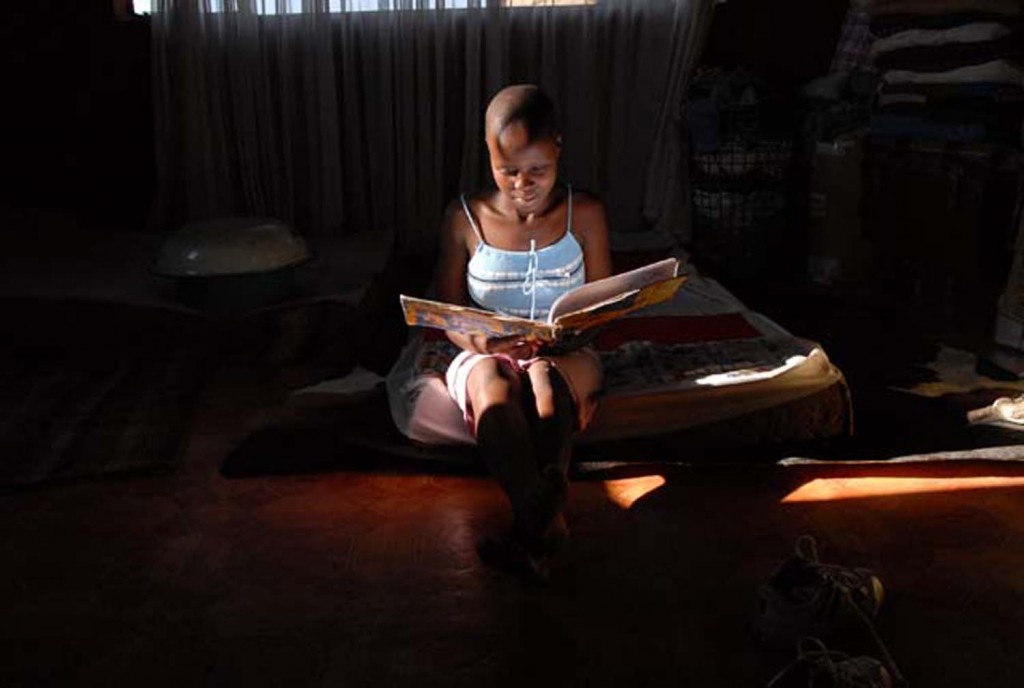

The names and images of gay and lesbian people interviewed cannot be disclosed because of fear of violence. This image is of Mpho Thaele, 19, an orphan who sells her body on the streets of Maseru, Lesotho. Photo © Eva-Lotta Jansson/UN-OCHA IRIN and Red Cross

“Gug” – short for “GayUganda” – maintains an internet blog where he writes about his life, giving personal anecdotes along with scathing commentaries about Uganda’s homophobic leadership. But he keeps his identity secret.

“Being with the man I love, I risk a life sentence, to make sure that the morals of the country are not destroyed by my “immorality,”

In Uganda, “carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature” is a crime punishable by life imprisonment. Authorities in many African nations would prefer to deny the existence of people like gug. Of 53 African countries, 38 have repressive government policies and sodomy laws that legitimize and encourage social discrimination, including unequal access to medical treatment.

This condemnation drives behavior underground, away from prevention and treatment services, thus increasing the risk of HIV transmission. It is fueling the epidemic on a continent that is already home to over 60 percent of those living with HIV/AIDS.

In Africa, men who have sex with men (MSM) are nine times more vulnerable to contracting HIV than the general population, yet programs of prevention, testing, treatment and care targeting same-sex-practicing people are still severely limited, if they exist at all.

The illegality of homosexuality discourages mainstream HIV/AIDS and human rights organization from publicly addressing the lesbian, gay, transgendered, and bisexual (LGTB) community and makes it impossible to collect crucial data on the prevalence of the disease and the social pathways by which it spreads.

“Research is the cornerstone of everything we do. It advances our knowledge, it advances our programming, and it is crucial to advancing our constitution,” Senkhu Maimane, a research project officer with OUT Africa, said. “If you have research, you have knowledge.”

The lack of research on the impact of AIDS in the African MSM community was, until recently, caught in a self-reinforcing cycle. Without the basic data needed to petition international donors for funding, the research didn’t take place. Of 561 studies of HIV in MSM communities in 2005, only 8 addressed same-sex transmission in Africa.

The US government’s PEPFAR – the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief – is one of the largest funders of HIV programs in Africa. Most of its $15 billion authorization was directed towards prevention programs in Africa; less than 0.004% of it for programs addressing MSM.

The limited research that has been conducted, however, revealed some consistent findings crucial to understanding and responding to the epidemic.

Many MSM do not identify themselves as gay, and engage in heterosexual relationships. Many have misconceptions about same-sex transmission that significantly increases HIV vulnerability. These include a false belief that HIV and other sexually transmitted infections cannot be transmitted through sex between men, or that only the receptive partner is at risk of infection.

In addition to inconsistent condom use between both heterosexual and homosexual couples, these practices and misconceptions drastically increase the risk of HIV transmission.

Laws, social norms and human rights obligations

“The denial of a set of basic human rights as a result of sexual orientation may well be the most significant social risk factor for same-sex practicing Africans.”

– International Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (IGLHRC)

Anti-homosexuality legislation is a crucial facilitator of sexually based discrimination It serves as a platform for the punishment of homosexual identity, often with language substantially vague so as to allow authorities broad leeway in policing unpopular sexual or social behavior.

In countries that do not criminalize homosexuality per se, other laws are often used to police sexual behavior and put gays and lesbians in jail. In Egypt and Kenya, for example, laws against vagrancy and loitering are used to round up suspected homosexuals. The majority of arrests of men and women on charges related to homosexuality are based on the presumed identity of the individual, not on the witnessing or reporting of illegal activity.

Lineo Makojoa, 15, at her home in Ha Majoro Village, Lesotho, holds the Memory Book that talks about her family. Her father died of Aids. Photo © Eva-Lotta Jansson/UN-OCHA IRIN and Red Cross

Despite the pervasiveness of these laws across Africa, long-term detentions are rare. More common are short-term arrests and extortion – usually the threat of exposure to police, family, or employers if payment of one kind or another is not made.

Gug, like many Ugandans, holds multiple jobs. While his sexual orientation is known to a few – members of his immediate family and very close friends – he is careful to keep his sexual orientation secret from his employers, saying that they would “not be very happy” to know that one of their employees is a gay rights activist and a gay man himself.

Verbal and physical abuse on the grounds of sexual orientation are common, and law enforcement authorities and government representatives have gone so far as to encourage citizens to abuse suspected homosexuals, who have little or no legal recourse. Police and law enforcement officials rarely intervene when suspected homosexuals are abused, discriminated against or verbally assaulted, while the vagueness of homosexuality laws has led to the dozens of arbitrary arrests across the continent.

“We are trapped in a lack of freedom,” gug says. “We cannot be self-assertive. Our sexuality makes us pariahs. Being open about it is simply not an option. Blackmail, extortion, loss of status, loss of clan, loss of self-respect – we risk all these things when we gay identify. Some of us have been cast out of our clan, and the clan is our identity. When it is taken away we have nowhere to go.”

The right to be free from unfair discrimination is protected by a number of treaties and charters to which all African countries are signatories, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. As signatories to these treaties, governments commit to uphold the rights of minority groups so that they will not face oppression.

“When three countries maintain the death penalty for consensual homosexual acts, they violate their commitment to international human rights norms,” IGLHRC Executive Director Cary Johnson said.

State-sanctioned homophobia is both served by, and feeds into, the belief that homosexuality is un-natural, not normal and, perhaps most critically, un-African.

“Arresting people, killing people, firing people from their jobs, kicking young people out of their homes – that’s what is un-African. Not homosexuality.”

– IGLHRC Executive Director Cary Johnson

The list of African leaders and officials that have used their platform to incite hatred against homosexuals is not short. Public statements by heads of state and high-ranking officials condemning homosexuality and inciting hatred and anti-gay violence have become common.

The most often quoted example is that of Zimbabwean President Mugabe, who in 1995 proclaimed that gays and lesbians were unnatural, subhuman and “behave worse than dogs and pigs.” In 1995 Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni, upon accepting an award honoring his governments efforts to fight HIV, said that male-male HIV transmission wasn’t a problem because “we don’t have homosexuals in Uganda.”

Last year, Gambian President Yahya Jammeh declared that The Gambia is a country of “believers” in which “sinful and immoral practices [such] as homosexuality will not be tolerated.” He promised “stricter laws than Iran” on homosexuality and said he would “cut off the head” of any gay person found in the country.

In his book, Off the Map – How HIV/AIDS programming is failing same-sex practicing people in Africa, Cary Johnson notes that such comments seem designed to inspire what he calls “a conspicuously xenophobic and nationalistic brand of homophobia.”

He points out that often the most vile and pointed attacks by African leaders have coincided with times of difficulty, and shift the focus away from social problems and economic distress.

Johnson believes that while decriminalization is a priority, what is more important is a basic shift in social attitudes and the behavior of authorities. He envisions this transformation resulting from individuals and organizations working within their own communities, at the family level, in schools, churches and mosques.

African LGTB groups are not remaining silent. Despite a lack of resources, many have launched HIV prevention, care and treatment programs with little, if any, external assistance.

“We are present,” gug said, “despite the best efforts of African leaders who insist on denying us our humanity.”