The Willow Creek homeless camp was in a shady grove near the start of a hiking trail, tucked behind a Sonic drive-in restaurant on the north end of the town of Madras, Oregon. The creek runs most of the year, and the willows screen the camp from the bustle of town. It’s a short walk to a Safeway supermarket. As far as homeless encampments go, it was ideal, and this one was home to a rotating cast of folks for the better part of a decade, most of them indigenous. The camp was about fifteen miles from the Warm Springs Reservation.

On June 11, 2024, the town began a sweep of the camp, clearing out several dozen residents. I spoke to a man named Gibson as he made his way up to the parking lot from the camp. When I asked his age, he jokingly referred to the medical band on his wrist from a recent hospital visit to verify that he’s 69.

Packing up his home and moving is hard, he said. “I got a nice set up. I got two tents, one inside of another. And then a tarp over the front for my porch. My sister, she’s got a big tent to move, a tent inside a tent, and a spot where she’s got a couch in there. Her tent has a queen-sized bed, and there’s another fold out bed outside on the covered porch.” What the city viewed as a nuisance was, for him, home

A 27-bed homeless shelter was recently built near the encampment by the Jefferson County Faith Based Network at a cost of 4.3 million dollars, which amounts to $160,000 per bed. It was funded by a combination of Community Development Block Grant funds, Executive Order money provided by the state of Oregon, appropriations money from Senator Lynn Finley, and the city of Madras. The local churches that make up the network seek to assist marginalized, disadvantaged, and vulnerable populations. The shelter provides dinner and a warm bed from 6 pm to 7 am, breakfast, and a sack lunch. Case management involves developing trusted relationships, identifying needs, barriers and challenges and an individualized plan.

When I asked Gibson if he would sleep in the shelter that night, he said no. He said he’d spent a night there once before, and was vague about why he wouldn’t go back. He set up his home somewhere else.

Similar problems are faced by the more than 653,000 Americans counted in HUD’s 2023 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report, a record high tally and an increase of 12% from 2022. The number of homeless people has increased steadily since the 1980’s, as housing became increasingly unaffordable.

The racial dynamic

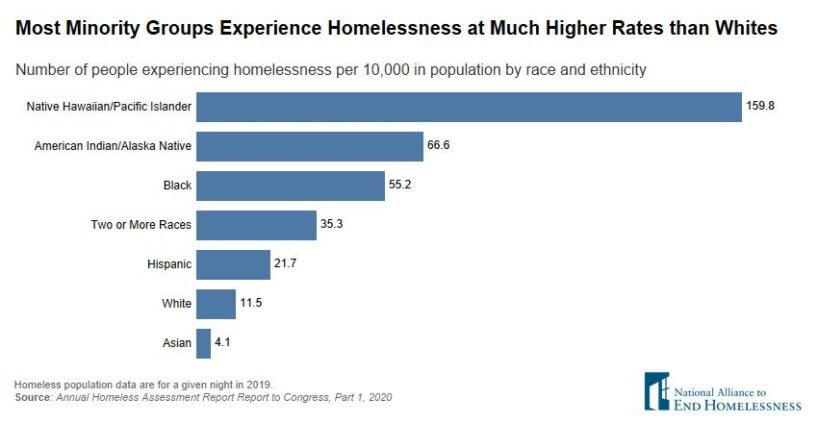

In the United States, people of color make up a much larger share of the homeless population than they do of the general population. Indigenous people, especially, are far more likely to experience homelessness. Seventy-five percent of the people served at the Madras shelter are indigenous from the confederated tribes of Warm Springs.

To find out why, I spoke with Tony Mitchell, Executive Director of the Jefferson County Faith Based Network, about the over-representation of indigenous people served at the shelter. “There are a lot of services and a lot of opportunities on the reservation,” he said. “But sometimes, due to challenges with drug and alcohol usage and that sort of thing, you have a combination of people who are houseless by choice and those that are houseless by need and circumstance.”

The perception that there are a lot of services and opportunities on the reservation is in stark contrast to the reality faced by people living there. According to the Warm Springs Community Action Team, challenges facing people on the reservation include a lack of affordable housing, poor infrastructure, the absence of living wage jobs, the poor state of the local economy, the virtual absence of thriving small businesses, low educational attainment, and wide-ranging public health and public safety issues. The poverty rate is twice that in the rest of Oregon, and a third of families live on less than $25,000 per year.

Sarah Saadian is the Senior Vice President of Public Policy and Field Organizing at the National Low Income Housing Coalition, an advocacy group focusing on the needs of extremely low income people. She explained that lack of affordable housing is the primary driver of homelessness, but there’s been a concerted effort to portray the problem differently.

“It’s reframing the issue so that it’s about people’s individual bad choices or moral failings,” she told me, but went on to say that, while recognizing that there are some people who have substance use disorders who need assistance, the best way to help those people is to make sure that they have a stable home to live in while they’re getting treatment and supportive services. “A lot of it has to do with wanting to punish people for their poverty, wanting an excuse for not investing the resources that we need.”

Mary Frances Kenion, Vice President of Training and Technical Assistance at the National Alliance to End Homelessness, agrees that there has been a persistent and intentional pattern of blaming the poor for their poverty which deflects from how systemic these problems are, saying that, “It’s an intentional approach that we’ve adopted as a society as an alternative to holding poorly-designed systems accountable. It’s so much easier to focus on an individual as opposed to questioning why it is that in certain communities, folks don’t have access to a well-paying job or a quality place to live or transportation, or why there are food deserts that exist in certain communities, or why there isn’t adequate healthcare for people to be whole and heal and support themselves.” This appeared to echo the challenges faced by those on the Warm Springs Reservation.

“There’s a connection between homelessness, racial discrimination, and systemic racism,” Saadian said. Federal funding of public housing to house low and middle income white families during a housing shortage in large cities began in the 1930s. As the GI Bill and other federal subsidies promoted the movement of white families to the suburbs, public housing was left to people of color who were then blamed for conditions that were the result of poor funding. Over that same time period, the racialized stigma against people who were in need of federal assistance, the trope of the “welfare queen,” was heavily saturated in racial stereotypes and biases. Racial stigmatization soured the public and also elected officials against the sort of funding increases needed to build and maintain public housing.

People in public housing today deal with problems with their roof and mold, pests and lack of heat. Saadian told me, “These are circumstances that nobody should be forced to live in, and a lot of that has to do with Congress failing to keep up with its responsibility to keep those properties in good condition.” Elected officials then blame individuals for those conditions when really it’s about the systemic failure to address the housing crisis and to invest resources.

“A lot of that failure has to do with really deep-seated racial biases and discrimination,” Saadian said. To the extent that public housing has challenges, it’s because Congress didn’t keep up with that funding in those investments for decades, she pointed out. “These are all policy choices that are being made, and nothing that’s innate to public housing that’s problematic.”

The United States has a long history of racial discrimination in housing. I spoke about this with Oregon Senator Kayse Jama, the Chair of the Oregon Senate Housing and Development Committee. A former Somali refugee, he told me, “Houselessness is absolutely a racial justice issue. American cities have been built on the exclusion and destruction of BIPOC communities.” He pointed out that from slavery, to segregation, to the age of mass incarceration, BIPOC folks have been largely excluded from private homeownership and quality public housing. These inequities were codified by law through redlining and racist lending practices which were integral to the establishment of the Fair Housing Administration in 1934.

The stigmatization of public housing as “monstrous, depressing places – run down, overcrowded and crime-ridden,” as President Richard Nixon said in 1973, was intentional and racially motivated. This stigmatization resulted in the passage of the Faircloth Amendment in 1998 which prevents the federal government from ever maintaining more public housing than was available in 1999. The United States has 63 million more people today than it did then.

National and local initiatives

But repealing the Faircloth Amendment would be half the battle. Senator Jama said that we also need a federal commitment to fully fund public housing authorities so that they can maintain safe, accessible, and affordable public housing for the people who need it. One of the major challenges is preserving the affordability status of housing units designated for low-income residents. Most state-subsidized public housing projects come with an “expiration date” after which units lose affordability restrictions and become market rate, often displacing the most vulnerable residents.

Over the next ten years, thousands of low income units will lose their affordability status so low-income people will effectively be kicked out of their homes and have nowhere to live. It makes little sense to build new affordable housing without also preserving the housing we’ve already built. Federal investment in new public housing development would free up state dollars to focus on housing preservation and the maintenance of existing units, Jama said. “Housing and homelessness are national issues that demand national solutions.”

Due to the lack of political will to fund and maintain public housing, the national strategy since the 1980s has been emergency homeless shelters which are funded by a combination of faith communities, FEMA, state and local funding, grants, and local groups like NeighborImpact and Housing Works. Kenion pointed out that even as we see the increase in those beds in the last few years, some people are not accessing them for a number of possible reasons, including paternalistic attitudes of staff, separation from beloved pets and partners, and a cold, institutional feel. But the main reason is that people want a home of their own.

Half of the beds at the new shelter in Madras are empty most nights. For the folks who were camped at Willow Creek, their campsite is their home – be it ever so humble – where their stuff is, where they can let their guard down, and relax out of the public eye. When asked what they would do with the 4.3 million dollars spent on the shelter on the hill, residents of the camp told me they would build a mansion, a house big enough for each of them to have their own room. What they want is a space and a place to call their own.

Housing First is a response to houselessness that prioritizes providing permanent, affordable housing and then offering services to help with substance abuse, mental illness, or other challenges. Kenion pointed to communities that are continuing to make progress despite the national increase in homelessness using this model. Houston, for example, has cut their homeless population by nearly two thirds since 2012. Newark, New Jersey, and Chattanooga, Tennessee, have seen similar success. “Those communities, and decades of research and evidence, support Housing First as the best policy choice.” Kenion added that veteran homelessness intervention has been implementing Housing First since 2011 and homelessness in that population has decreased by nearly 50%.

But instead of putting resources into building deeply affordable public housing, many communities have increasingly criminalized homelessness through camp sweeps and making it illegal to sleep, sit, or even eat in public spaces despite the absence of adequate alternatives. The Grants Pass vs.Gloria Johnson case, decided by the Supreme Court in June 2023, reinforces the criminalization of homelessness. Gloria Johnson was given a citation for camping in a park and was prohibited from sleeping in her van. Her claim that municipal codes such as these violate the Eighth Amendment against cruel and unusual punishment, since there were no low-barrier shelters she could access in Grants Pass, was rejected.

Regarding the case, Kenion said that the court’s decision to hear the case had come amidst the growing wave of criminalization across the nation. “This is really threatening people who are experiencing homelessness. It’s threatening their civil rights. It’s threatening their dignity. And it’s not addressing the root causes that we know have led to this crisis.”

The heavy police presence at the Willow Creek camp sweep was symbolic of the criminalization of homelessness. I caught up with Tracey, a 20-something indigenous woman, as she walked away from the camp rolling a suitcase behind her. “I don’t understand why they’re doing this. We have to be somewhere. Why all the police? We’ve always followed their rules.”

The sweep comes in the wake of a long history of displacing Black and brown people and of gentrifying neighborhoods. Less than six months after the opening of the emergency shelter nearby, Willow Creek was slated to become a city park next to a trail system.

Kenion talked about taking power out of the hands of the poor. “How do we return power to people that have been historically minoritized and excluded from every aspect of society? If we can figure out ways in which to solve racial justice issues, we might be able to solve homelessness overall, for everyone.”

Top photo: Homeless camp, photo by Elizabeth Garbee CC 2.0