Click here to listen to the companion podcast

Remembering Hasankeyf

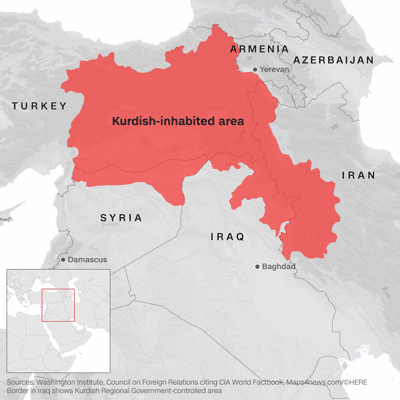

Until 2020, the town of Hasankeyf was one of the world’s oldest continuously inhabited settlements, with over 12,000 years of history that survived the rise and fall of civilizations and empires. Hasankeyf is in in the cradle of civilization, the area spanning southeast Turkey, Northern Iraq, and Northern Syria, which is also be the roughly defined area of Kurdistan. In the region where humankind’s first civilizations cropped up, Hasankeyf was a relic of ancient history. It is now submerged under water.

From 2006 to its completion in 2020, Turkey began constructing the Ilısu Dam with the goal of generating hydroelectricity. The construction of the dam, on the Tigris River, was a part of the ongoing Southeastern Anatolia Project (Güneydoğu Anadolu Projesi, GAP), which aims to promote social and economic growth in Turkey’s rural southeast, home to the majority of Turkey’s Kurdish population. But the construction of the dam would leave the town of Hasankeyf underwater, along with its centuries of history. For many, the dam symbolized Turkey’s desire for control over water, over people, and ultimately, its tenuous relationship with the Kurdish people.

“It is not really a dam which is necessary for energy production, irrigation, or modernization,” says Joost Jongerden, an associate professor of rural sociology at Wagenigen University. “It’s a dam, which somehow tries to, I think, demolish, to make us forget about a history which precedes the history of the Ottomans, which precedes the history of Turkey. A history which tries to emphasize the world and history which could be associated with Kurdistan.”

Despite fierce opposition, both at home and abroad, the Ilısu Dam was completed in 2020. The local majority-Kurdish population was displaced and relocated to Yeni Hasankeyf (New Hasankeyf), which overlooks the submerged city. Some of the cultural artifacts were also preserved, but at what cost?

The Southeastern Anatolia Project

The Tigris and Euphrates rivers are “the lifeblood of Kurdistan,” says Bnwar Abdulrahman, a conservationist and environmental activist for Waterkeepers Iraq/Kurdistan. For generations, the rivers have shaped the way of life, but in recent decades the Tigris and Euphrates have been poorly managed by surrounding nations, who have struggled to come an agreement on how the water should be shared. Each nation has attempted to maximise their share of the river at the expense of the environment and the people. But with the origin of the rivers located in Taurus mountains of southeastern Turkey, the nation exercises a unique level of control.

“There’s a lot of interest working around nationalist dam building. In the post-colonial context, dam building has been used to celebrate the emergence of a particular regime or this idea that countries are modern and able to harness the rivers,” Leila Harris, the co-director of the Program on Water Governance at the University of British Columbia, told me.

The desire to develop southeastern Turkey is not new. The southeast, also known as Northern Kurdistan, has historically posed obstacles to Turkish nation building due to the presence of Kurdish opposition. Its distance from the central government has also meant that the state has struggled to bring it under its control. For a young nation seeking to define its identity, this meant trouble. The Southeastern Anatolia Project served as way to simultaneously harness the power of the rivers while also addressing the “Kurdish issue.”

The GAP was initiated during a time of intense conflict between the Turkish state and the Kurdish Workers Party (PKK). Turkey’s persecution of the Kurdish population dates to its early history. It saw forced displacement and assimilation, along with massacres, such as the Dersim Massacre. After the military coup of 1980, the new administration under General Kenan Evren, ramped up the repression of Kurdish rights. For instance, Kurds were categorized as “Mountain Turks” in act of cultural homogenization. In August 1984, the PKK attacked Turkish military targets in southeastern Turkey, marking the beginning of a militarized conflict between the two. Since 1984, the conflict between the PKK and Turkey has claimed the lives of roughly 30-40,000 people. The state further escalated its repression of Kurds as a counterinsurgency strategy. For instance, Kurdish language was banned from public and private spheres until 1991, though some restrictions still apply. After the conflict resumed in 2015, at least 350,000 people have been displaced, according to the International Crisis Group.

In addition to official measures against Kurds in Turkey, some have also suggested that the GAP (which began in 1989) was part of a broader counterinsurgency strategy against Kurdish resistance. Along with forced displacement and increased militarization of the region, projects aimed at developing the rural countryside – such as the construction of dams – brought periphery communities under tighter control of the state. The southeast, with its Kurdish majority, has historically shown greater levels of support for the PKK. By controlling water, the state can exert influence over the Kurdish population and strengthens its authority in a region where it historically has struggled to maintain control.

Joost Jongerden says that displacement is more than just collateral damage or punishment. “What I try to argue is that this evacuation of the villages must been seen in the context of an attempt of the Turkish state, to somehow develop a new rurality, a countryside of which it can exercise control.”

But what does tightening control look like in everyday terms? The GAP and its associated dam constructions have disproportionately affected Kurdish communities in Southeast Anatolia. The Ilısu Dam, for instance, is estimated to have displaced at least 78,000 people along with erasing parts of history. Resettlement and compensation plans have also been poorly executed. One example of the state’s failure to adequately compensate those displaced involves the issue of land deeds. Many displaced residents held informal land deeds that were not recognized by the state so they, along with tenants and sharecroppers, were not entitled to compensation.

The GAP has also militarized the southeast, where dams became “walls of water” to prevent guerilla infiltration from Northern Iraq/Iraqi Kurdistan. To make matters worse, the GAP has under-delivered on many of its key promises.

Consequences

Humanity’s first civilizations developed near the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, with agriculture thriving due to flooding events that distributed sediments and nutrients throughout what has been called the Fertile Crescent. Flood security is one benefit of damming as flooding events become more predictable and easier to manage. But Leila Harris says that damming also disrupts the natural cycles that are important for agriculture and ecology,. The consequences also extend to communities living along rivers.

The impact of the Southeastern Anatolia Project is not confined to Turkey’s borders. Iraq relies heavily on downstream flow from the Tigris and Euphrates, which accounts for roughly 98 per cent of its water supply. Much of Iraq’s water flow is now up to Turkey’s discretion. The Associated Press reports that, in 2012, Iraq received an average flow of 625 cubic meters of water per second from the Tigris River. In 2021, the flow decreased to just 36 per cent of that level, which Iraqi water ministry officials attribute to decreased rainfall and the effects of damming. Coupled with worsening climate change, the construction of dams upstream has left Iraq with a severe water crisis. Over 7 million people are at risk from water scarcity.

On top of 1.2 million people displaced by war, the International Organization for Migration reports that at least 130,000 individuals across central and southern Iraq have been displaced to drought conditions. These challenges are only exacerbated by the aftermath of decades of conflict in Iraq. “While all of these countries were building dams and infrastructure for cutting and diverting the water, Iraq was busy with war, regime change, ISIS, internal conflict, and corruption,” Bnwar Abdulrahman explained.

Water quality is another key concern. In 2018, violent protests erupted in Basra due to poor public services, including water access and quality. Over 100,000 people were hospitalized due to poor water quality. Of course, Turkey’s dam building is not the only cause of Iraq’s water challenges, but the combination of mismanagement by the state, poor water practices, inadequate infrastructure, climate change and the lack of transnational cooperation over water usages continues to threaten people and the environment.

Rethinking the relationship with water

The consequences posed by the Southeastern Anatolia highlight the need to rethink water governance both regionally and globally. The water crisis in Kurdistan, exacerbated by dam construction, highlights the need for more responsible and ethical water management practices.

Water should not be seen as a resource to be exploited for economic gain or geopolitical leverage. Instead, water must be understood as a vital element with its own rights and intrinsic value. We cannot continue to take, take, take, and act in blind ignorance towards that harm that we are causing. On the state level, this means moving towards more transparent and sustainable water governance practices.

“There are always trade-offs,” said Leila Harris, “And so it’s a question of how do we value different trade-offs? We just have to be dealing with those in a more justice-oriented framework, where we understand if we’re asking communities to deal with the losses, we take that seriously and also compensate to the extent that one can compensate for some of those losses. And that’s still not going to be enough in some cases, of course, but it would be a step in the right direction. Rather than assuming that these are all just goods, which is often still the discourse around dams. I think we’re way beyond the point in time that we should be pretending that the dams only deliver benefits.”

“Fair use of water is the most important thing to make everyone realize that you use the water, but the water is not yours,” Bnwar Abdulrahman said. “Your downstream neighbours also benefit from it and also need this. And this applies to the individuals in the region all the way up to the communities and all the way up to the countries in the region.”

I had the privilege of listening to Bnwar recount his experience working on the project, “Reconnecting with Our Lifeblood.” Along with a team, Bnwar traveled from the entry point of the Tigris in northern Iraq, down to the port of Basra, in the south. The goal of the project was to document the ways in which people connected with the rivers. He told me about visiting Chibayish, a town in the Iraqi Marshes.

“One of the most amazing experiences I had in my life was visiting the marshes and seeing indigenous people still living there,” he said. “Even after all of those wars happened, all of these environmental issues, they are still there, and they are still trying to live and adapt and continue their life. And it also just filled me more and more with desire to continue this work. Because at the end, even if it’s indirectly, my work here at Waterkeepers will impact those communities down there. It will be very nice to have them survive these issues and overcome them, and thrive. There were still issues but it was amazing for me to see that spirit of surviving and trying to adapt and overcome.”

The Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, flowing through the heart of the ancient Mesopotamian cradle, are not just vital water sources. They are living symbols of history, cultural and endurance. For millennia, these rivers have nurtured civilization and remained deeply embedded in the cultural identity of the region. They are the lifeblood of agriculture, providing sustenance in a challenging landscape, and have been central to the development of communities from the Kurds of Hasankeyf to the indigenous Arabs in the Mesopotamian Marshes. However, these rivers, once celebrated for their bounty, now face an uncertain future.

It is imperative to shift towards fair water practices that prioritize the protection and sustainable management of rivers. This includes rethinking large-scale dam projects, shifting towards cooperative transboundary water governance, and recognizing the intrinsic rights of the river. Otherwise, the tragedy of Hasankeyf will be repeated.