Taj Rowland is a business owner and father of two in Utah. Upon meeting him, one might be convinced he is a born and bred American. Yet his past is far more complex than meets the eye.

“I remember being put into a van, then later transferred to a jeep, and driven about three hours away until we reached the orphanage,” Rowland said in an interview for this article. Born with the name Chellamuthu, he was one of thousands of victims of the trafficking in children for profit.

Opportunities for adoption fraud arise in several ways. Birth documents could be falsified to receive payments for non-existent children. Middlemen may prey on uneducated parents, convincing them that their child will be placed for education and returned thereafter. Birth parents may even choose to sell their children to traffickers. Generally speaking, such cases are the consequences of insufficient adoption protection measures and the misinformation of people involved.

After using what seemed to them a legal process to adopt a young girl from a Christian orphanage in India, Taj’s American parents were surprised to learn they were to welcome a seven year old boy, he says. “The night before I was supposed to get onto a plane and come to America they realized they were getting a new child and it wasn’t a young girl.”

In the 1970s, when Taj arrived in US, there was a growing interest for parents in higher-income countries to adopt from abroad. The doctrine surrounding foreign adoption involved moving children from resource-limited to resource-abundant settings. At that time, it wasn’t a topic of debate. The adopting parents weren’t considering that their actions were doing anything other than humanitarian good, let alone encouraging child trafficking.

History and development

In the US, domestic adoption wasn’t considered socially acceptable for a long time. The first major policy recognizing adoption as a legal action, on the basis of child welfare, was passed by Massachusetts in 1851.

Many children were left orphaned following the US-Vietnam war. In this photo, American soldiers visit a Christian orphanage in Vietnam in 1969. Photo: US Marine Corps

Even more taboo was the idea of transracial adoption, as most Americans preferred families of unified race for the purpose of concealing the adoption. Black children and parents were disproportionately affected by this stigma, having been excluded until after other transracial adoptions became commonplace. The first documented transracial adoption in the US was in 1948.

Intercountry adoption formed from what were originally foreign missions’ efforts to re-home war orphans. Events like those in West Germany, Japan (1945), Korea (1953), Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos (1975) soon became a new possibility for prospective parents to build a family. In 1982 there were almost 6,000 foreign children adopted by Americans alone, with Europeans and Canadians becoming similarly involved.

Although adoptions of all kinds became increasingly popular after these events, the process did not occur openly. Parents would provide their information to social workers who would then, through a series of organizations, match them with a child. From then until today, closed adoptions – meaning those that occur without contact between prospective and biological parents – are commonplace when adopting abroad.

Early measures

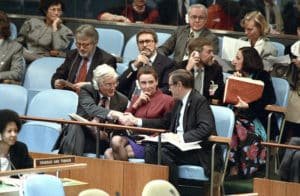

UN and UNICEF officials shake hands following the adoption of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, 1989. Photo: United Nations

The first major international document detailing the rights of a child (the UNCRC) came into effect in 1990. Following suit was The Hague Convention on Adoption (1993), which defined global safeguards for orphaned and adopted children. Countries who ratified the convention, according to Robin Pike, executive director at Choices Adoption, “are agreeing to adhere to the highest standards of adoption practice that are possible.”

These conventions have had mixed results. On the one hand, there was a surge in adoption agencies, resulting in “many players involved in any one single adoption and lots of eyes on the documentation that came along with the child,” says Pike.

Consequentially, in 2004, almost 30,000 children were documented as having been legally adopted from abroad.

On the other hand, Hague Convention countries are legally allowed to adopt from non-convention countries. Therefore, the documentation involved with a child under adoption is subject to different “adoption language,” as Pike describes it, meaning different internal legislation, practice, and procedures.

Today, while more certifications of orphaned children are required in the adoption process, there exist multitude of reports that outline cases, anywhere from Cambodia to Ethiopia, of children suffering under the guise of adoption.

There are those who openly address systemic issues families face. “I believe that there’s a lot of truth in poverty playing a role in the reason why some families cannot preserve themselves,” says April Dinwoodie, Chief Executive at the Donaldson Adoption Institute. As a transracially adopted person herself, Dinwoodie is proud to speak about the issues within the adoption space, particularly when it is falsely treated as an industry.

Yet tackling the issue of money as a driving force in the adoption process remains vastly complicated. Some reformists have suggested using the poverty standard as an indicator for determining whether parents are ready to enter adoption. By doing so, family preservation assistance could be allocated to troubled parents before any child be relinquished and the international adoption avoided altogether.

On the receiving end, prospective families can spend up to $50,000 on all necessary procedures. The sheer price of engaging in this process makes it difficult to speak of intercountry adoption without money being central to the conversation.

Significant decline

Since its peak in 2004, the number of children adopted from abroad has gone down by 74%. Although not for certain, this decline is indicative of a decrease in intercountry adoption fraud.

Furthermore, the decline has surfaced concerns with how countries treat children under adoption. As of 2007, China instated strict policies for prospective parents abroad, including prohibiting single homosexual women and people who are morbidly obese from adopting. Russia, in 2013, closed adoption doors on North America, presumably as a way of protesting against gay rights activism and the US for condemning its human rights abuses.

Such actions by countries, Dinwoodie says, are in the spirit of treating children as “commodities that we can turn off just as much as a trade agreement.” The result is a significant worldwide disproportion of children in foster care than are adopted.

Dinwoodie believes “this is a human rights issue,” and that it is “imperative to know where we come from for a healthy identity development.”

But what exactly does that mean? For the UNCRC, a crucial element is its inclusion of “cultural rights.” This notion extends the importance of a child’s right to a family by drawing on such things as identity, nationality, and non-discrimination. The Hague Convention, additionally, draws upon the importance of ensuring the best interests of a child under the cooperation of all relevant stakeholders between states.

The delays or barriers that foreign policies create have the potential to impose significant mental distress on prospective adopted children. In Canada, parents can expect to wait anywhere from several months to years to welcome a child from abroad to their home. Ideally, a child should be given sufficient time for the appropriate cultural integration.

Alternatively, it is difficult to call into question the importance of other policies. Under The Hague Convention, six months should be spent trying to find a permanent family for a child who is legally available for adoption before they leave the country. Pike believes this is good for children abroad, as it “means more children are being raised in their own country and culture.”

Taj’s identity development was, as he recalls, a long and challenging issue. Surprisingly, he considers his experience a positive one, as it gives him the opportunity to better inform prospective parents and children on easing the process.

“Being an adult, and having gone through this experience, having children of my own, I feel I have been a better person for it” he says.

Much as it is the right of a child to have a family, it is the right of a person to have a child. As Dinwoodie has experienced, parents are prepared to “do it at any cost – literally and figuratively.” On the receiving end, she recommends changes that make the adoption process more transformational. “It starts with good education and awareness and moves throughout the life cycle of everyone.

Roland Selinger

During the summer of 2015 Roland was interning at LVCT Health, in Nairobi, conducting socio-demographic research on the most at-risk populations of HIV/AIDS in Kenya.