Avaaz supporters at a protest to protect the Amazon from clear-cut logging. More than 2 million people signed the Avaaz on-line campaign petition.

Photo: Avaaz

Avaaz, the online campaigning organization, leads the largest global movement on the web. Is online campaigning the future of activism?

In 2011 Indian activist Kisan Baburao (“Anna”) Hazare declared a fast unto death unless the Indian government agreed to allow civil society to draft a new anti-corruption law. 500,000 Indian citizens joined the Avaaz campaign supporting his call for reform in less than two days, and the Indian government agreed to Hazare’s demands.

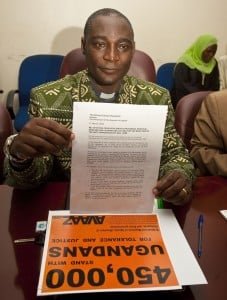

When a Ugandan MP proposed an anti-homosexuality bill that carried with it the death penalty for certain homosexual acts, 1.6 million Avaaz members signed an online petition opposing it, while tens of thousands more contacted their respective heads of state. The bill was shelved.

Avaaz also joined efforts to establish the world’s largest ocean preserve, block an Amazon-destroying mega dam in Brazil, and change climate change policies in Japan, Germany and Canada.

Founded in 2007, Avaaz – meaning “voice” in several languages – has about 10 million members across 193 countries with a mission to “close the gap between the world we have and the world people everywhere want.” It employs 15 full time campaign staff, and is supported by a network of thousands of volunteers.

Brianna Cayo Cotter, Media Campaigner for Avaaz, says that the group did face scepticism when it began. “They said it wouldn’t work, that it would never get off the ground.”

The group takes advantage of the global reach afforded by the internet to overcome the traditional constraints on the scale and scope of single-issue social movements. As its website says: “Avaaz has a single, global team with a mandate to work on any issue of public concern – allowing campaigns extraordinary nimbleness, flexibility, focus and scale.”

Canon Gideon Byamugisha with Avaaz campaign signatures and a petition calling for rejection of an anti-homosexuality bill. An Anglican priest with a parish outside of Kampala, he was the first religious leader in Africa to publicly announce that he was HIV positive. Photo: James Akena

Azaaz campaigns focus on “tipping-point moments of crisis and opportunity,” Cotter says. There has to be the possibility of success. “If there is no potential for action, for change, then there is no Avaaz campaign.”

The Avaaz approach means that everyone has to wear more than one hat, she says. “In the morning you’re working on a campaign to save the whales, and that afternoon it’s Murdoch’s takeover of BSkyB.”

Praise for the organization has been forthcoming. The German newspaper Suddetsche Zeitung described Avaaz as “a transnational community that is more democratic, and could be more effective, than the United Nations.”

Micah White, senior editor of Adbusters magazine, disagrees. “Avaaz is playing a game of diminishing returns. They are trying to attract the greatest number to click their link knowing that these same people will increasingly stop engaging in the organization.”

He believes that the “clicktivism” of Avaaz will be ruinous to activism in the long run.

“I think activism should be hard. People should be angry about things. They should look around and try to change it. And they should realize that it’s going to take a lot more than the internet to do it.”

Danni Young, a human rights and conflict resolution analyst, doesn’t have the same concern, although she isn’t an Avaaz member, and prefers to get involved directly with the causes she supports.

“If an activist stops all other political engagement in favour of his or her internet connection, the problem is not clicktivism,” she says. “The problem is the lazy activist.”

When the topic comes up with Brianna, she is resolute. “I know what the criticism is. They call Avaaz a clicktivist organization, and call what we do clicktivism. But my response is, just look at what we’ve accomplished.”