Chen Qiulin watched as half of her hometown, the ancient city of Wanxian, was submerged in water by the creation of China’s Three Gorges Dam, the world’s largest electricity-generating plant. She has memories of her childhood home in a large residential compound and of the old harbour she once played in with friends after school, both gone now. “It became a new city with very many high buildings. I hardly recognize it anymore,” she said.

Colour Lines was shot in Zhongxian County, the last place to be submerged. While Chen is depicted wearing an angelic dress, Wu Hung notes that in the video Chen doesn’t feel angelical at all. Rather it seems as though she is revisiting a historical environment to which she is intimately connected.

For five years, Chen’s life was consumed by the drastic changes around her. Motivated to document the transformation of her surroundings, this contemporary artist created four videos corresponding with the four phases of construction. Rhapsody on Farewell (2002), River, River (2005), Color Lines (2006) and The Garden (2007) are part of Displacement: The Three Gorges Dam and Contemporary Chinese Art exhibition shown at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago in 2009 and more recently at the Nasher Museum of Art in North Carolina.

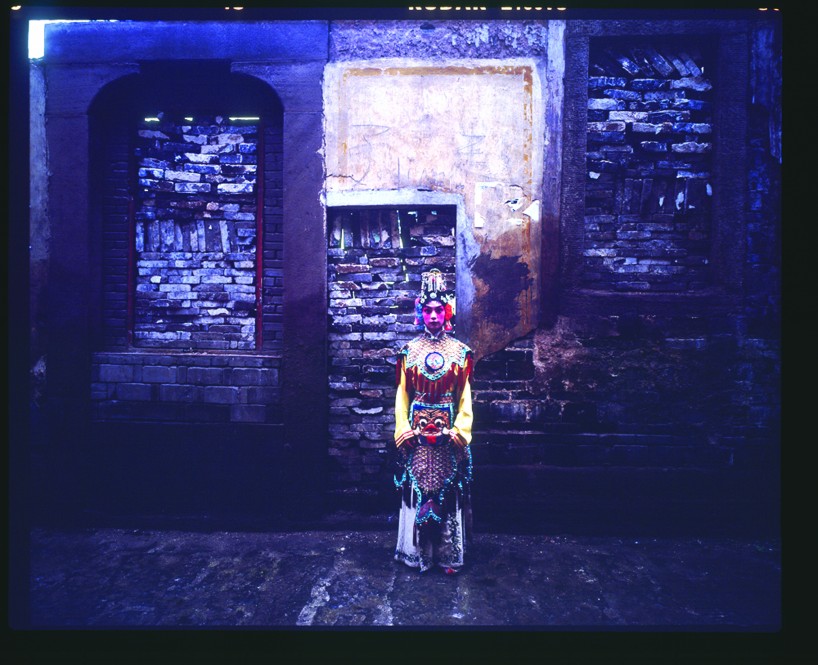

The main theme running through the four videos is displacement. Smart Museum Consulting Curator and expert in East Asian art Wu Hung described Rhapsody on Farewell as depicting the resulting irritation and powerlessness. In writing about the exhibition, he said that Chen conveys these feelings through distorted self-portraits, first dressed up as a tragic figure from the ancient story Farewell My Concubine, Consort Yu, twirling amid broken houses and then in black and white as a young girl running across the screen.

Conflicting feelings about the past and the future largely disappear in River, River, in which rapid urbanization occurs as a flood of water covers the land. Contemporary high rises are built, providing people hope for a better future.

Uncertainty returns in Colour Lines. Of particular significance is the scene where Chen appears as the spirit of an old building that is about to be destroyed. Her decision to remain in the broken city highlights two competing emotions: the natural tendency to hold on to the past and the desire for a fresh start.

The fourth video, The Garden, brings hope for renewal. Migrant labourers carry huge bouquets of peonies around the city. Life has largely returned to normal and has arguably even improved. However, as the ghosts of a historical couple from the legend of The Romance of the White Snake appear and quickly depart, there is an air of melancholy as it becomes clear that the ghosts represent the history of the city.

The Three Gorges Dam is controversial. The elevated water of the reservoir reportedly improved navigation along the Yangtze River, which comprises of 80% of China’s inland shipping, but critics argue that silt and sediment accumulation upstream will render the Yangtze impassable, clog ports and intensify flooding. Up to five million people were displaced by the project, and critics say that that the energy produced will not be harnessed efficiently because of engineering limitations, but the dam has helped control flooding.

“The Three Gorges Dam project on the Yangtze River has withstood its biggest flood-control test,” the People’s Daily Online English Edition reported in July. “It has managed to contain the raging flood waters as the Yangtze River rose to levels not seen in over a decade. The inflow volume is 20,000 cubic meters greater than during the catastrophic Yangtze floods of 1998 when 4150 people died and 18 million were evacuated.”

Originally created for another exhibition, Rhapsody on Farewell was made using Chen’s family’s video camera. It is the most intense film of the four, as Chen recalls being overcome with sadness and anger as the home of her childhood memories was destroyed. The sadness reminded her of the tragic opera, Farewell My Concubine, which she incorporated into the film by dressing up as Concubine Yuji, depicted above.

“I cannot really say if the huge change caused by the rapid urbanization is good or bad,” Chen said. “My point of view is to always be faithful to what I feel, from the sadness in my early works to the calmness in my work now.”

Of the four artists in the exhibition, Chen is the only one directly affected by the Three Gorges Project. Her ability to present a personal perspective is what she feels makes her work unique. “Their works analyzed the conception of urbanization after what happened. I lived in one of the small towns that were affected, so I was able to record the changes I saw and what I felt. Maybe in the far future, children will say ‘So that is how our city used to look, that is how the elder generation used to live,’ when they see my work.”

Instead of harbouring an activist agenda, Chen assumes the role of an artist. Guo-Juin Hong, of the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at Duke University, noted that spectators at the Nasher Museum attempted to label her as somewhat of a witness to an environmental catastrophe, which wasn’t her goal. “For her things are happening that she cannot stop, but her role as an artist was to be a part of it. That’s a very important distinction to note.”

In contrast to Rhapsody, River River is more positive, and accepting of change. Even so, there is still the nostalgia for the past, reflected in the juxtaposition of modern and traditional images. Photos courtesy of Chen Qiulin and the Max Protetch Gallery.

Is it possible for her art to not be political? Lian Duan, Coordinator of Chinese Programs at Concordia University, admits this question is tricky. “To me, her work is, in a way, political although she herself may not accept this idea. Today, environmental issues are very political.”

The Chinese government has itself remained largely silent about her work. As China continues to rise to superpower status, the international media keeps a watchful eye on human rights abuses, Guo-Juin Hong said. Permitting a certain degree of criticism is a smart way to manage public opinion, particularly with regard to those with an international reputation, and presents the government in a positive light.

Despite media attention and growing recognition, Chen says that she knows little about how her work is being received internationally. “I am just a normal person making art in China.”