An explosion and fire nearby led officials to explore an abandoned munitions building in Guatemala City, where written, audio, and photographic documents on a wide range of police matters from as early as the 1900s were stored. A Guatemalan team funded by Switzerland, Spain, and Germany is cleaning, organizing and making digital copies of the documents, many of them disintegrating with age and exposure to moisture. The files can be used as evidence in the victims’ legal cases, and their discovery contributes to fighting impunity in a country where human rights abuse and corruption are still common.

Photos courtesy the Guatemalan National Police Archive Project

More than twenty-five years after Edgar Fernando Garcia, labour leader and father of a one-year-old girl, disappeared from outside his relatives’ house in Guatemala City, suspects in his abduction have been identified and detained.

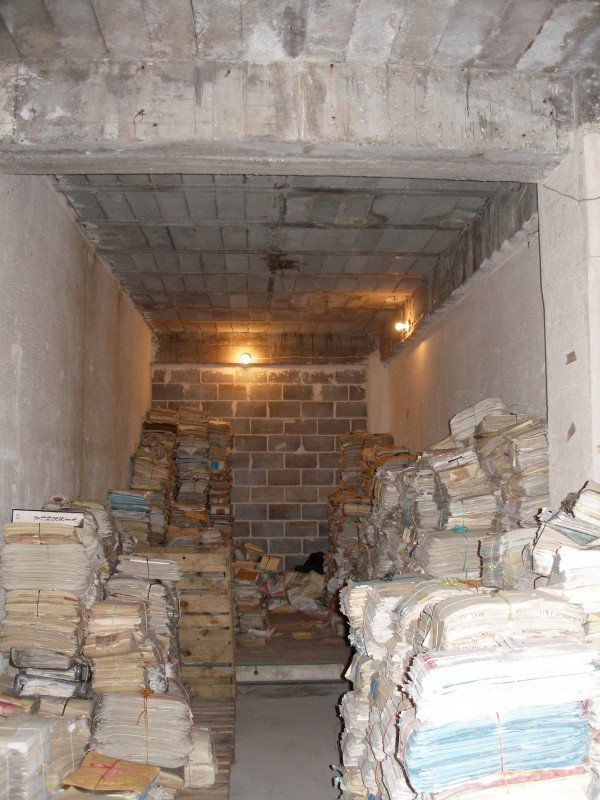

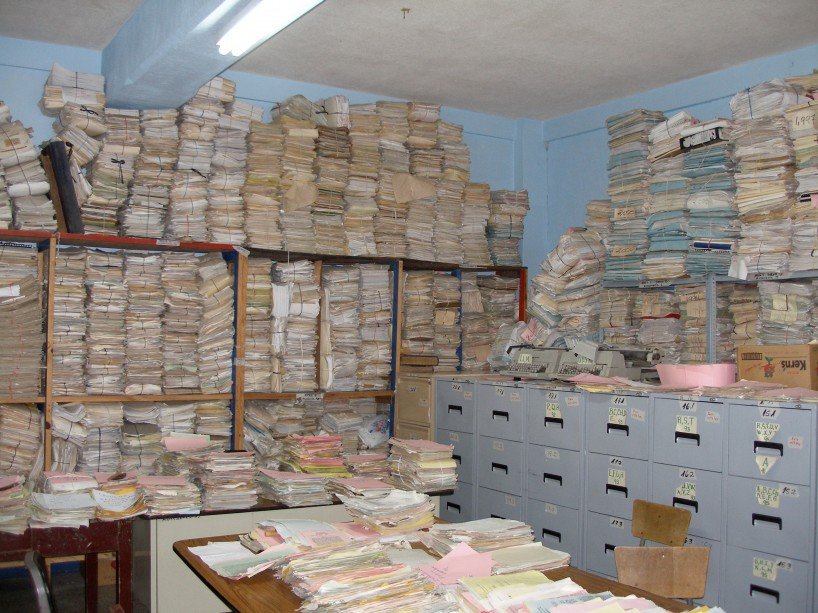

In March 2009, senior police officer Héctor Roderico Ramírez Ríos and retired policeman Abraham Lancerio Gómez were arrested as suspects in Garcia’s disappearance. The arrest was based on evidence accidentally discovered five years ago in an old munitions dump in Guatemala City. The abandoned building contained 75 million pages of secret national police documents, many of which provide information on police actions during Guatemala’s violent civil war. It is estimated that 400,000 people disappeared and 200,000 were killed between 1960 and 1996.

Documents among the stacks of decomposing and mouldy paper indicate that Garcia was abducted as part of the state-sponsored violence that mainly targeted community leaders, most of them Mayan, and trade unionists that the government perceived as threatening.

The day Garcia disappeared, he left his house to go to a market in Guatemala City. He and his family planned to celebrate his aunt’s wedding anniversary in that afternoon in February, 1984. He never showed up. Instead, soldiers arrived to take his belongings away. No official explanation followed. No government investigation took place to find out what had happened.

Garcia’s daughter, Alejandra Garcia Montenegro, now a lawyer, is taking his case to court using the newly discovered evidence. “I wanted to become a lawyer to fight the injustice in the country and because of my parents,” she said.

Concealing the evidence was part of a larger operation to conceal information about police activity during the armed conflict from the Guatemalan public, censoring written information and by controlling the media. Now, President Alvaro Colom, elected in 2007, supports making the archives public and accessible.

An explosion and fire nearby led officials to explore an abandoned munitions building in Guatemala City, where written, audio, and photographic documents on a wide range of police matters from as early as the 1900s were stored. A Guatemalan team funded by Switzerland, Spain, and Germany is cleaning, organizing and making digital copies of the documents, many of them disintegrating with age and exposure to moisture. The files can be used as evidence in the victims’ legal cases, and their discovery contributes to fighting impunity in a country where human rights abuse and corruption are still common.

Photos courtesy the Guatemalan National Police Archive Project

Alvaro recently removed the Human Rights Ombudsman’s exclusive control over the archives, allowing access by the public. The restoration and declassification of the files’ contents can be a dangerous process. Human Rights Ombudsman Sergio Morales’ wife, Gladys Monterroso, was abducted and assaulted hours after he released the first report on the contents of the police documents. Human Rights activists Article 19 believe that Monterroso’s abduction was intended to intimidate Morales and was directly related to the report, which implicates the national police in human rights abuses committed during the civil war. Morales has also received threats, and he and the team working on the archives are subject to physical attack and other acts of intimidation.

Resistance to the declassification of the discovered documents is suspected to come from perpetrators of human rights abuse who have remained in powerful police and government positions.

“Half of the people in government were horrified by the discovery of the documents,” says Kate Doyle, director of the National Archives project. Impunity, corruption, and human rights abuse remain prevalent in Guatemala.

Alejandra Garcia knows that she might lose the case and the police officers may be acquitted despite the evidence from the archives. After twenty-five years of not knowing what exactly happened to her father and of unfair treatment by the government, she wants closure.

“I can forgive, but I have to know whom.”