Listen to the companion podcast on the Human Rights Magazine channel

While the children of military leaders are studying in foreign countries, soldiers are dying tragically, former child soldier Ko Aung Ko Htwe told local media when he was released from prison in 2019. Abducted at a railway station, he was forcibly recruited into the Tatmadaw, the Burmese National Army, when he was fifteen years old. After he escaped the military two years later, he was charged with the murder of a motorbike owner and served ten years in prison. Even though Ko Aung Ko Htwe was lucky enough to escape the fate of serving in the military, he faced constant threats and human rights violations. After being released from prison, he spoke on Radio Free Asia about being forcibly recruited and abused by the authorities before the first trial. He was then arrested again and charged with violation of Section 505 (b) of Myanmar’s Penal Code, a clause regarding political incitement. By silencing the victims, the Myanmar government aims to conceal the issue of recruitment and use of child soldiers from the international community and to maintain a positive image on the global stage.

Overview: slow upturns and quick downturns

The 2002 Human Rights Watch (HRW) report “My Gun Was as Tall as Me” described how children in Myanmar are often coerced, intimidated, and deceived into joining the Tatmadaw. The military processes recruits through Su Saun Yay (recruit) camps, where the child soldiers go through medical checks and registration and wait until the military’s training school receives them. In recruit holding camps, contacting families is denied and forced labour and arbitrary punishment is quite common.

Once in a training school, children undergo four and a half to five months of training in which they may be forced to conduct or witness cruel acts against civilians without knowledge of what and for whom they are fighting. Isolated from the outside world, they are deprived of the promised salaries or even basic nourishment and are brutally beaten or given exhausting labour once they fail to obey instructions. This engenders deep-rooted physical and psychological damage.

Children forced into military service encounter challenges in leaving the military due to the constant fear of arrest or potential execution. For those that manage to successfully flee, their future remains uncertain and unpredictable. Many deserters attempt to escape across the national border, and some are recruited again, into resistance groups.

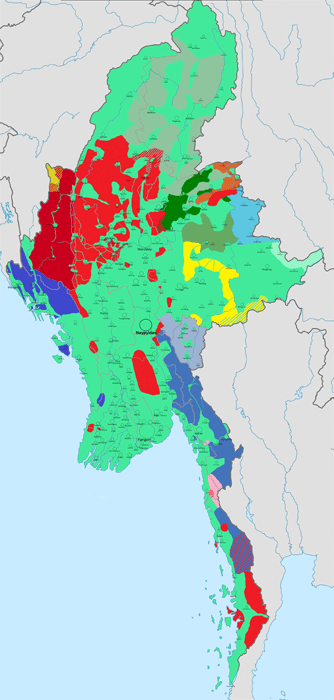

The atrocities against children are done by both Tatmadaw and ethnic resistance groups, especially in Kachin, Shin, and Kayin states. However, the use of child soldiers in Tatmadaw was far more significant than all the opposition groups combined as opposition groups are more popular among civilians and meet fewer difficulties with staffing. Most resistance groups would still admit children who volunteer even though some have policies about the minimum recruiting age, while some expressed their interest in demobilizing their child soldiers. For instance, in November 2020, a Joint Action Plan commitment “to end and prevent the recruitment and use of children” was agreed between an ethnic Karen insurgent group, the Democratic Karen Benevolent Army, and the UN Country Task Force on Monitoring and Reporting on grave violations against children.

Myanmar has a long history of recruiting children into the armed forces, and it was listed as the country with the highest number of child soldiers by HRW in 2002. Underaged children accounted for 20% or higher of the serving soldiers that year, according to the testimonies given by ex-soldiers to the HRW.

From 2011 to 2021, under a civilian government, the situation slightly improved and there were observable patterns of cooperation between the UN and the Burmese government. In June 2012, the Myanmar government signed the Joint Action Plan with the United Nations, which aims to end and prevent the recruitment and use of children by the Tatmadaw. A more strict and regulated age assessment procedure was established, and responsible military directives were implemented. Nevertheless, there were concerns regarding the large gaps between the government’s promises and the actual efficacy. Human Rights Watch contended that in the year following the signature of the Joint Action Plan, the Myanmar government failed to address the fundamental issue, which is the system of incentives behind unlawful recruitment and the lack of accountability among the military. The UN access to the armed forces for verification purposes was denied as well, and authorities sought to exempt and justify the recruitment of 16-year-olds who had completed 10 years of education.

Eventually, 956 children were released and reintegrated. In 2015, the government signed and ratified the optional protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child on the involvement of children in armed conflict, which endeavours to prohibit all forced recruitment of children below the age of eighteen. In February 2017, the government signed the Paris Principles on Children Associated with Armed Forces or Armed Group and relaunched the campaign programs.

After the takeover of a military coup in 2021, the situation worsened as armed conflicts escalated, and the effectiveness of these agreements became questionable. More resistance groups were created, and the dynamics changed rapidly, making it difficult for the UN to track accountability. I spoke with Ariane Lignier, Communications Officer for the Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict (SRSG-CAAC), who told me that in 2021, 280 children were verified to be recruited and used in the army, and then slightly lower -235 children – in 2022.

In 2020, the Tatmadaw was delisted for underage recruitment and use in the UN Secretary-General’s annual report on Children and Armed Conflict, yet on 5 October of the same year, two Muslim boys were apparently killed when they were used as human minesweepers during a crossfire between the Tatmadaw and the Arakan Army. The Tatmadaw has repeatedly failed to make effective investigations it has promised.

The International Labour Organization has also noted an increased prevalence in the forced recruitment of young persons by groups aligned with the Myanmar military, especially in the ethnic areas. The UN Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights in Myanmar, Thomas H. Andrews, expressed his concern, in his 2023 report to the Human Rights Council, that there will be a return to the widespread use of forced and underage recruitment by the military.

Causes and interlinkages

To find out more about the fundamental causes of this issue, I spoke with Dr. Alexandre Pelletier, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Laval University, who specializes in Southeast Asian politics. He also serves as the co-director of the Observatoire des Droits de la Personne (Human Rights Observatory). He talked about how the decentralization of armed forces and their lack of funding and workforce contribute to the abuses of civilians, and how lower-ranking military officers are ordered to meet recruitment requirements. After the forceful suppression of the 1988 pro-democracy protests, there was a significant decline in the number of individuals volunteering for military service, yet the size of the army expanded. This stems from the raised recruitment quota. Just recently, according to an article from Radio Free Asia in October 2023, the junta increased quotas of militia training and conscriptions in the Ayeyarwaddy region, and so teenagers were also forced to join.

More broadly, Dr. Pelletier suggested that the widespread poverty and displacement could contribute to the recruitment and use of child soldiers. The availability of drugs and the overall lack of functioning schools also made the situation more difficult for children. Myanmar’s economy is affected by steep inflation in essential commodity prices, inadequate infrastructure, and frequent scarcities in necessities. This causes children to depart from their families to look for jobs and avoid becoming financial burdens. Hence, children who are deprived of essential survival needs and alternative opportunities sometimes join resistance groups voluntarily in seek of a brighter and more secure future. Some children are motivated by the need for self-defense, or seek revenge for their families who have been killed or displaced by the Tatmadaw. According to HRW, opposition forces, including the Shan State Army (South), Karen National Liberation Army and the Karenni Army, have stated policies against recruiting children under the age of 18, but appear to accept children who claim to voluntarily join their forces, adding to the complexity of the situation.

Dr. Pelletier told me that the absence of proper legal frameworks also worsens the situation as there is no enforcement of human rights and accountability of military officials, and it is likely that the Myanmar government does not have the capacity or the willingness to prosecute changes. The Tatmadaw has vehemently denied that it forcibly recruits children and has attributed the concern to minors lying about their ages and to “slanderous accusations” by the West. Meanwhile, the government has implemented propaganda efforts and has been cracking down on human rights activists and civilians who start legal cases against local government officials.

Alongside the formal recruitment of child soldiers, Tatmadaw arrests children as a strategy to undermine the resistance movement and non-aligned groups, Dr. Pelletier told me. He said that, “The Assistance Association for Political Prisoners of Burma has reported that at least 658 children were arrested by the Tatmadaw and at least more than 350 are still in detention.”

According to testimonies of ex-child soldiers, one of the general strategies of illegal recruitment is to approach unemployed and adolescents who are on their own in public places and ask for identification documents, knowing that most adolescents do not carry them. The military officers then threaten to imprison them unless they enlist in the army. “

I also learnt from Ms. Lignier that the issue of recruitment of children intertwines with some other violations, like sexual violence and human trafficking. She said that there is an observable connection between human trafficking and recruitment and use of children, yet specific figures are to be researched.

The Special Representative of the Secretary-General for Children and Armed Conflict, Mrs. Gamba, has been cooperating with the Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Myanmar to investigate the interlinkages of the recruitment of children with other grave violations, Ms. Lignier told me.

The future

Dr. Pelletier suggested it is crucial to break down the structure of incentives for the recruitment and use of child soldiers among military officers. Now, children are sold as commodities in the recruit market, with recruits sometimes bought from civilian brokers. A former child soldier, Maung Zaw Oo, described in a 2007 HRW report that, “The corporal sold me, and later I learned that a recruit costs 20,000 kyat (about US$20 at the time), a sack of rice, and a big tin of cooking oil.” Underaged recruitment is often associated with money-hungry officials and businesspeople, and this system of incentives must be addressed, Dr. Pelletier said. He also mentioned that the more fundamental solution is to enhance the level of resources and education, which would lead to an improved human rights situation and alleviated recruitment. However, this is difficult to implement in the short term. He said that, although the Tatmadaw does not have enough capacity to make quick improvements, the National Unity Government is concerned with its credibility and legitimacy in the eye of the Western international community and has at least asked its members to prevent the recruitment of children.

UN organizations are trying to continue the engagement and discussion with the Myanmar government to push for the implementation of the Joint Action Plan, Ms. Lignier said. “As the Myanmar government does have an action plan with the UN, we are in regular contact with the Myanmar armed forces to see how they’re implementing the actions and the measures that have been jointly identified.” As the resistance groups are often organized along ethnic lines, and conflicts between ethnic groups are common, the SRSG-CAAC is also working closely with the Office of the Special Rapporteur for the Prevention of Genocide. She also told me that the SRSG-CAAC is working closely with the UN Security Council Working Group on Children and Armed Conflict, along with regional organizations such as the Association of Southeastern Asia, to seek solutions through collaboration. Nevertheless, it is the Myanmar government that is responsible for implementing international humanitarian law and SRSG-CAAC can only track the dynamics of the conflict, to advocate for changes and to provide verified information to UN Member States.

Isabella Aung, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Political Science at Queen’s University specializing in Burmese politics, has also expressed her concern and is not optimistic about what the military government will do. “There is no official indicator that the regime is still working with any international organization to keep its promises,” she said, “But there’s a lot that the regime can do. It can adhere to all the Action Plans and agreements it made, but it is not likely that anyone can tell a military what to do because the regime has a mind of its own and does not regard the underaged recruitment as an issue.” She also expects to see an increase in the recruitment and the use of children in the conflict areas since there are no laws or policies in place and practiced by the junta to protect the children. In terms of actions in the international community, she suggested that what the international community can do is to promote awareness of the situation and to put pressure on the military junta, and to name and shame their practices. “As long as it is not a zero-tolerance policy that can directly affect the regime, the regime couldn’t care less,” she said. She is also concerned that news regarding the situation is not regularly covered in mainstream media and has been inadequate since the military coup.

“Children just shouldn’t be in war,” Aung said when I asked about her personal feelings towards the child soldier issue in Myanmar. Indeed, the war has caused irreversible and deep-rooted physical and psychological damage to children, and as Ms. Lignier also said, “The situation is extremely worrying, as the situation in Myanmar was one of the most deteriorated in 2022. But every child deserves to grow in peace and opportunities and hope.”