Wednesday

I arrive in Washington at noon, depressed as I consider the financial crisis and what it will mean for people in impoverished countries. It’s time for the main policy meetings of the World Bank and IMF, and NGOs like me take part in some of the dozens of meetings that are planned.

I take the metro from the airport to the guesthouse to drop off my bag, and within an hour I’m at my first session, on gender and income. It’s not a hopeful start. Money from production goes increasingly to corporate profit, and less to wages, and the financial bailouts are reinforcing inequalities.

Next up is a session on “Broad Community Support” at the International Finance Corporation (IFC), the World Bank division that funds private sector projects. The talk about community support comes down to the tension between “consultation” (required by IFC) and “consent” (not required). There is a gradual shift by companies and the IFC to seeking “consent” of people affected by a project, but there are problems. Most countries don’t have adequate standards of consultation let alone consent, the IFC staff determine how a community is to be consulted rather than the community itself, the IFC doesn’t know how to gauge consent, and communities are usually divided on support or opposition to a project.

Despite all the rationalizing about why the World Bank doesn’t do better, the talk is all about rights and empowerment and it’s lifted my mood considerably. Until recently the World Bank didn’t engage in this kind of talk at all.

On my way back to my room that night, I buy a copy of Street Sense from a gregarious guy who asks for a bit extra for it “since it’s my last copy.” Street Sense is the local newspaper sold by the homeless, and it is everywhere. I give the vendor an extra dollar and start to cross the street. Before I get to the other side, I hear him calling out again, “Street Sense, get your Street Sense, my last copy.” On the other side there is another vendor, a quiet, older guy in a wheelchair. I buy another copy.

Thursday

The day starts early with a session on accountability in World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) projects. An NGO study showed that IDB projects scored much worse than World Bank projects in terms of good practice. Weak quality control practices were identified as the probable reason.

Then I join a discussion at the World Bank’s Inspection Panel, which investigates for social and environmental impacts. “There is a new emphasis on accountability driven from below… We don’t mention human rights. Should we?” Even without an explicit mandate to examine rights issues, the Panel has taken them on in terms of indigenous peoples, livelihood and water, inclusion and participation, and security of the person.

Walking to the Inter-American Development Bank, I stop to chat with Conchita Piccioto. She’s been living on the sidewalk in front of the White House since 1981, day and night, in her permanent protest against nuclear arms and an array of other issues. Today she is entertaining a group of Japanese tourists, who seem delighted. American tour groups tend to get nervous and avoid her, As she often does, she gives an energetic and scornful analysis of US policy, her dark eyes glinting below the safety helmet she always wears (she has been assaulted several times).

Vinita Watson is the IDB Executive Director for Canada. I knew her from meetings in Ottawa, when she was with the Department of Finance, but this is my first meeting with her as Canada’s representative to the IDB. She is personable and it’s just the two of us so our talk is pretty informal and open. She takes an optimistic approach, applauding recent increases in our government’s financial support of the IDB. She recognizes that sometimes dealing with borrowing member governments can be difficult, but thinks it’s best for the Bank to stay engaged. She sees the IDB as moving to more inclusiveness and considerations of social impacts in its projects, and says that having the IDB fund a project helps because its processes and mechanisms provide social and financial safeguards.

Next: the IMF session on the G20 and the financial crisis. The room is big, and filled with perhaps 80 NGOs. The IMF is eager to lend after a period of declining relevance. Lending is up by half, to US$2.2 billion, and they want to get it up to $3 billion a year. The IMF says conditions are fewer and less onerous, NGOs say the reality is different, and countries like Turkey, Hungary and the Ukraine were told to tighten their belts.

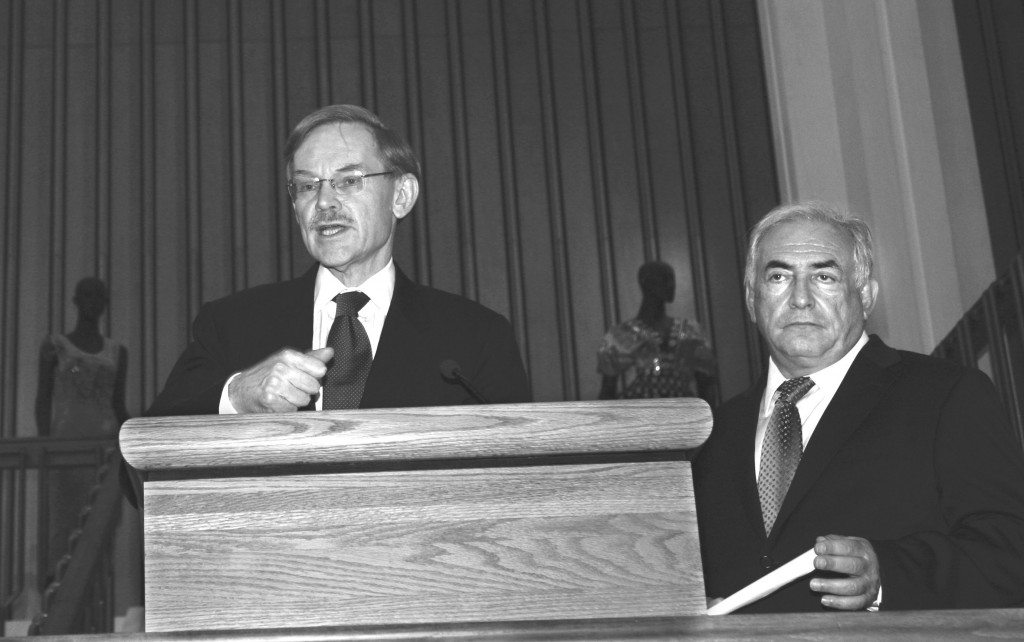

In the evening there is a reception for NGOs hosted by World Bank president Robert Zoellick and Dominique Strauss-Kahn (DSK), the head of the IMF.

DSK says the IMF is now in “Version 2.0,” with streamlined processes and less conditionality, although he also said that “economic adjustment during the current crisis will be painful, adjustment is always painful.”

He reminds us that the IMF has launched a “Fourth Pillar” in its governance reform process, which will allow for NGOs to have some input into the process. The SJC was actually key in this. The IMF announced the Fourth Pillar in its response to a letter I wrote to DSK pointing out that the reform process entirely excluded civil society participation.

DSK was asked about using some of the IMF’s gold stockpile for debt cancellation for the poorest countries. He said it’s too complicated, and they can’t commit it for that use. Then he told the hundred or so NGOs that he had met for an hour with Bob Geldof earlier that day, but now was running late and had to leave.

Zoellick stays longer, comments that water is the emerging crisis for the world, and he wishes that was the global priority rather than the financial crisis.

Friday

First up is a panel discussion on people with disabilities. The speakers focus mainly on access to services, and don’t have an international policy perspective, so I am getting restless. Then the discussion turns to HIV/AIDS and dynamics of sexual activity of people with disabilities. Ahead of me are two older fellows, one blind and the other in a wheelchair. The blind guy nudges the other and they quietly laugh together, huddled over a copy of Playboy – in Braille.

I talk a bit with Mary Ennis, Executive Director of Disabled Peoples International, about World Bank policies and how much needs to be done. Then I take part in a session on World Bank information disclosure policy, which is being updated, and the need for better monitoring and evaluation of projects. It’s one of the main subjects for these meetings; this session is one of several.

At lunch I speak a bit with a person from the IMF’s External Relations. “The Social Justice Committee? Ohh… the letter!” She means the letter that sparked the Fourth Pillar process. She seemed impressed.

Outside the IMF a guy with a bullhorn is rapping about being black in America as people stroll by amused. The police nearby ignore him.

In the afternoon I have a meeting at the Canadian office at the World Bank, with Samy Watson, Canada’s Executive Director (ED) at the World Bank, and Michael Horgan, our ED at the IMF. They represent constituencies that include Canada, Ireland and some Caribbean countries. I expect to be the only NGO there, but Watson’s office has scheduled an American NGO for the same meeting. That NGO sends a contingent of some ten people that, along with the EDs and their staff of about six people, completely fill the meeting room. I’m the only one that provided an agenda of what I want to discuss, and that’s pretty much toast now. But the discussion eventually gets going and is pretty helpful. Changes to the World Bank’s disclosure policy is a main topic, and the need for a new approach that assumes transparency.

On debt cancellation, Watson agrees “in principle” on the need to cancel odious or illegitimate debt; for him the question is what mechanism to use, since none exists now.

Horgan admits that IMF warnings about problems in the US economy weren’t loud enough, and showed the need for better early warning systems for global finance. He says Canada is one of the countries most in favour of greater transparency.

Both Horgan and Watson say they are in favour of strengthening the “voice” of small and poor countries, by reforming the voting process at the World Bank and IMG and changing how decisions are made.

I stay a while after the meeting for some informal chatting and information gathering, then go downstairs to a workshop on the financial crisis. There will be an increase in the debts of poor countries, and aid funds are shrinking. I say that IMF assistance is costly to the borrowers, that the G20 commitments were mostly loans, not grants, and included over-optimistic trade finance projections. Part of the difficulty for poor countries is that the debt relief they’ve gotten so far did not provide the “robust exit” from financial problems that was originally promised.

Another session on the financial crisis, and the role of the IMF. On grants versus loans, the IMF argument is that with grants fewer countries benefit and the amount available is limited, and grants from the World Bank are slow in arriving, so it’s better for poor countries to borrow from the IMF.

Time for a coffee break, and an interview for community radio with the only other Canadian NGO in town, from Ottawa. Jim Flaherty, the Minister of Finance, walks by and waves hello.

The next session, on disclosure policy, is not in the World Bank’s main building, but in another nearby. I’m surprised to see a photo exhibit featured in the lobby, of Nigerian militants in oil-producing areas of Nigeria, along with an impressive display of African art and carvings from the World Bank’s collection. There is a large turnout – perhaps fifty NGOs. The World Bank official heading the review agrees that the current requirement for government permission before anything is public “should disappear.”

Then it’s my last session, on Africa and the financial crisis. Twenty people, mostly African, and the mood is not happy. They worry about the future – how can Africa compete? In America the tractors are air conditioned, in Africa farming is by hand. They are frustrated by the setbacks Africans are facing – they have had other crises, but this one especially was not their doing. There is a lot of money flying around, but how much will be for Africa?

As for the other crisis, climate change, for Africans the discussion it is not about reducing carbon emissions. Their concern is that, whatever the promises to reduce emissions, there will be strong impacts for which they are not prepared.

In the main rooms upstairs, finance ministers from around the world take turns making speeches, and main policy directions are summarized in communiqués. The IMF plans to double lending to low income countries. The World Bank plans to triple its lending, to US$100 billion over the next three years. The financial crisis has given the institutions new strength, and they are raring to go.

The meetings come to an end.