Roxanne Solas one of 250,000 foreign domestic helpers living in Hong Kong. Photo: Jillian Kestler-D’Amours.

Roxanne Sonas had hopes of a bed during her stay with the family that employed her, but she slept on the floor. Her employer promised her that a bed would arrive when they changed apartments.

“On the day we moved in, they had IKEA deliver a cabinet,” the 33-year-old Filipino domestic helper said, her eyes filling with tears. “It was horrible.”

Sonas slept on top of the cabinet, without a pillow or blanket, in the living room of her employer’s home in Hong Kong’s trendy Causeway Bay neighborhood for five months, while she worked up to 22 hours a day, six days a week.

“Luckily it was summer so it wasn’t cold,” Sonas said. “I was very afraid. I was always crying.” After an arduous process involving the police and the Hong Kong labor department, she was eventually able to quit.

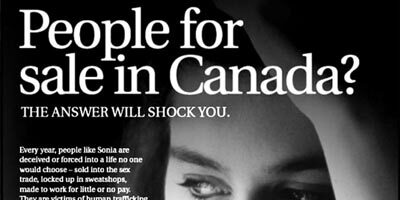

There are laws to protect foreign domestic helpers living in Hong Kong, most originally from the Philippines, but enforcement is not easy. Helpers that have signed contracts dating after July 2008 must be paid at least $3,850 HKD ($545 CAD) per month.

They are also entitled to one rest day per week, to be fed or receive a food allowance, and depending on their years of service, and receive between seven and 14 days of vacation time annually.

Despite the laws, at least 15 percent of foreign domestic workers in Hong Kong are underpaid. Approximately 27 percent are verbally and physically abused and 22 percent do not receive weekly days off. Helpers for Domestic

Helpers (HDH) is an organization that provides free paralegal advice and counseling to domestic helpers in Hong Kong. The workers come from several countries, the majority from the Philippines but increasingly from Indonesia. 95 percent of Indonesian domestic helpers that come to HDH for advice report being underpaid, with only one or two days off per month. In addition, when a contract is terminated, foreign domestic helpers have only two weeks to find other arrangements or they must leave Hong Kong. This leaves little time to deal with grievances or collect owed wages, and deters abused workers from leaving their jobs.

Many workers are placed by an agency. The maximum commission an employment agency may collect from a foreign domestic helper is no more than ten percent of the helper’s first month’s wages. In reality, however, many employment agencies impose substantial placement fees on helpers for months after they have arrived in Hong Kong.

On Sundays, many domestic helpers have the day off. The downtown area of Hong Kong island is closed, which lets helpers meet each other, talk and play games right on the streets. This photo was taken during the 111th Philippines Independence Day festivities on Sunday, June 14.

Photos: Jillian Kestler-D’Amours

Sonas, for instance, paid nearly 90 percent of her monthly wages to an employment agency for three months, keeping only $500 HKD ($70 CAD) for herself each month. “If you pay or not, you still lose your job. So I stopped paying,” says Sonas, who eventually got back her money after three long meetings with the agency.

Mhel Beagan, a domestic helper from the Philippines who has lived in Hong Kong since 1983, counts herself lucky to have “not just an employer-employee relationship” with the family she works for.

“The government doesn’t know what’s going on inside the employer’s house. The helpers tolerate it or keep quiet because they’re afraid of being sacked. It’s really a day-to-day contract because the employer can terminate it at any time.”

Still, not being considered a true Hong Kong resident after over 25 years here weighs on her. Most persons living in Hong Kong for seven consecutive years are eligible for permanent residency, but not domestic helpers.

“The Hong Kong government doesn’t take into consideration our cases, which is very sad indeed,” Beagan said, sitting with a dozen other Filipino domestic helpers over a lunch of steamed rice, pork and vegetables. “It’s very important to have the support of friends. We support one another morally and spiritually. We help each other.”

Eventually, with the help of other domestic helpers and local volunteers, Roxanne Sonas was able to get out of her abusive work environment once. She now works for a Canadian family living in Hong Kong, and volunteers her time to help other domestic helpers that are struggling.

“Experience is my best teacher,” she says. “I comfort them and advise them according to my experience. They are afraid, and I’ve been there.”

Sonas now earns $4,100 HKD ($581 CAD) per month, works eight-hour days, has access to a computer and television set and, perhaps most importantly, has her own bed. “It’s very comfortable,” she says, smiling widely. “I’m happy.”