Ten years have passed since UN Human Rights Council endorsed the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGP). Corporate social responsibility has become a mainstream view that serves as a standard for the company to modernize its policies, as “soft laws,” crafted as normative statements, became instrumental in raising the overall awareness for human rights abuses.

However, without a legally binding agreement, major challenges remain as businesses in developing countries face difficulties seeking a balance between profitability, productivity, and social responsibility. In newly industrialized countries that pursue a labour-intensive production process, the management system tends to put the workplace condition and worker’s rights as the least important considerations.

Large manufacturing firms: a military management system

I spoke with with a production line worker from the largest Foxconn factory, located in Longhua Town, Shenzhen, who I will call “Jessica.” She was a short-term dispatch worker in the company’s massive industrial area, where hundreds of thousands of people are employed making, among other things, iPhones. After she finished a two-month production line experience, on Chinese social media she wrote, “Although I had a lot of bad experiences at Foxconn, I do not regret working there, it was an experience that enriches my life.”

When I spoke with her, Jessica said that she has mixed feelings towards Foxconn. For many rural-urban migrants who do not have a higher education, Foxconn seems like a dream place to work. Foxconn never delays wage payments. Most importantly, it helps workers pay for social insurance (China’s social insurance system includes endowment insurance, medical insurance, unemployment insurance, employment injury insurance, maternity insurance, and housing provident fund). However, the management system of giant transnational corporations can be inflexible, and sometimes manufacturing factories use a military management style to ensure productivity.

2. Due diligence should be implemented and conducted to prevent and mitigate business-related human rights violations.

3. Businesses should provide remedial action to contest adverse human rights impacts.

Jessica found it difficult to endure the harsh management system. “I feel like we were treated like machines, not human. We were always under supervision, we were watched by the workshop manager at the production line, and dorm supervisor at home watched us.”

The intensive management system ensures that there is absolute obedience and consistent discipline. Jessica says that some managers are arrogant and uncivil, but workers prefer to just comply with the regulations rather than going against the managers. Foxconn adopts Taylorism in its production system, in which complicated jobs are divided into small, simplified pieces, the procedure is standardized, and productivity is maximized with minimal input. Workers are strictly trained as “parts” of the entire production system and not required to think strategically; instead, they are expected to repeat monotonous and tedious tasks.

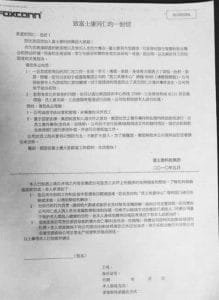

“A Letter to Foxconn colleagues”

Foxconn workers are to promise not to commit suicide.

At Foxconn, most workers must work overtime to fulfill the production target. In order to ensure high productivity, Foxconn runs on two shifts, day and night. 75% of workers have an average four-day break each month, 8% of workers have less. 73% of them work at more than ten hours a day, and on average work 83 hours of overtime a month. But as Jessica says, “It is actually not a bad thing to work overtime. If we reject working longer to meet the production target, we will never get a chance to work overtime.”

A regular worker’s salary has four components: the base wage, overtime pay, year-end awards and performance awards. The base payment is around 1200 yuan ($240 CAD). On average, 43% of wages come from overtime pay. “We earn a very low base wage, so we must work extra hours to support ourselves. We cannot miss any overtime working opportunity. Otherwise, the manager will cross our names out from the list, and we will never get a chance to earn that overtime premium. This is the reality at the production line, we are working for the company, but we are also working for ourselves.”

China’s Labor Law states that overtime work should not be more than 36 hours per month (article 41). However, excessive overtime working is not considered illegal at Foxconn; the company requires workers to sign a pledge to show that overtime working is voluntary. Similar contracts include a pledge to not commit suicide, which states that families will not receive compensation from the company if a worker commits suicide, since that would damage the company’s reputation. Such contracts are obviously outside of what is required in the Labor Law.

The standards of the UN Guiding Principles could be supported by civil society organizations, including labour unions, which represent workers and monitor business violations of human rights. Civic organizations are also assumed to be essential stakeholders in the grievance mechanism. Jessica seems unfamiliar with civil society organizations; she believes that China’s NGOs are incapable of representing the factory workers. The labour union is an organization under strict government controls, which also lacks the transformative capacity to change the current situation. Indeed, China’s civil society organizations often work as extensions of government policy; they are service providers but unlikely to become advocates for business-level “counter-hegemonic movements.”

Foxconn’s case uncovers several weaknesses that exist in the UNGP. First, the principle does not create a new legal obligation that allows the company to enforce. Countries like China have legislation on labour-related issues, but they are often undermined and ignored by large business owners who have greater bargaining power. Large transnational corporations that have private contracts with employees have loopholes to escape the obligations laid down in these legislative measures.

Second, the UNGP assumes a robust public sphere. We must recognize that civil society can create both positive and negative externalities depending on the types of social capital they produce. Bridging social capital helps achieve horizontal relations of reciprocity, but bonding social capital enhances the exclusivity of associational life based on group interests.

Third, the UNGP assumes workers are aware when they experience human rights violations. In reality, most manufacturing workers are unclear about their rights, and they believe that the grievance mechanism is not access for justice but a risk of losing jobs.

Small and medium-sized companies – a better place?

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) form the backbone of the global supply chain for large businesses. Large businesses choose factories in newly industrialized countries to minimize cost. Factories producing simple and less sophisticated consumer goods have a competitive advantage in low labour costs. The conventional understanding is that SMEs are more deprived of resources to implement human rights policies than the larger ones. Yet, the capacity for SMEs in developing countries to address human rights issues has been underestimated.

Daolong owns a B2B nanotechnology company in China. His factory produces extensive products, including fabric for bags and suitcases, protective clothing and masks, and cloth interlining. “There are only two standards that the clients take into consideration. The first one is quality, and the second one is cost efficiency,” Daolong says, noting that corporate social responsibility has never been a standard used by clients to pick their business partners. “Corporate social responsibility is currently not a norm in China. The government has not particularly stressed companies to put human rights protection in our agenda.”

At Daolong’s factory. A different corporate culture in small and medium enterprises?

In recent decades, although more Chinese businesses have incorporated environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues into their decision-making to follow the global norm, the results are mixed. SMEs still focus more on profitability since disclosing social responsibility reports is costly but not mandatory.

Daolong highlights the importance of China’s social insurance system that provides a basic social security guarantee for factory workers. China’s social security law requires employers to register the new employee with the local Social Insurance Bureau and the Housing Fund Bureau. Both employer and employee are obligated to make contributions, but employers typically account for a larger share, and they must pay insurance for themselves and employees on a timely basis.

“In reality,” Daolong said, “Many workers are not willing to pay for the insurance system; they would rather keep that cash to spend.” The central government promulgated the system, but in actual practice local governments only require the company to pay insurance for a limited number of workers to grant them legal status. So, in Daolong’s factory, there are some workers unwilling to pay for the insurance, and the state’s social security law does not protect them. Daolong sees it as the company’s responsibility to encourage the worker protection. “We would sometimes educate our workers about the importance of paying these insurances, and now almost everyone is willing to start paying.”

Nevertheless, according to Daolong, SMEs tend to have a more compassionate management system than large companies. He believes that workers’ rights are well-protected by the company even though such obligations are not stated in formal terms. “Everyone in my factory has been working together for a long time; there is definitely attachment between us,” he said. “Labour disputes rarely happen to us.”

From Daolong’s perspective, corporate culture in SMEs plays a vital role in shaping the employer-employee relationship, in which workers and owners tend to have a closer relationship, with a high degree of personal interactions ensuring that the executive team effectively hears and addresses labour’s voices.

Pressure from within society

Civil society engagement is essential for establishing and protecting human rights norms. Civil society organizations demonstrate a bottom-up behaviour with its constant assessment of public affairs and its rules and actions. Internally, the horizontal collaborations between members within civic organizations allow an individual to voice their remedial request.

For her perspective, I spoke with Jasmine Zhang, a labour rights activist at China Labor Watch, a New York-based NGO seeking to help China’s workers become more informed of their rights and empowered to realize those rights within their communities.

China Labor Watch assesses labour practice in Chinese factories.

Zhang says that there are many other factors that should be considered besides the size of the workplace when we measure corporate’s accountability to the employees. “My personal observation is that maybe developing a point system to assess all disadvantages/risks that could lower the standards of workers’ condition could be helpful. For example, is there an accessible labour dispute mechanism for workers? What are the time and financial costs for workers to defend their rights? Is there a direct, anonymous grievance channel in the workplace?” She would like both public sector bureaucrats and the civil society activists to develop a mechanism that accurately measures ESG performance in the private sector.

“Many of the Guiding Principles or U.N. Conventions are not very practical or useful for workers that we interact with on a daily basis,” she said, partly because most unpaid or child workers have a lack of understanding on how to protect their rights or get out of an abusive situation.

In many underdeveloped, labour-intensive regions, local governments lack the incentive to implement legislative measures to regulate human rights abuses in the private sector. Such measures require a higher operational cost at the corporate level, which would adversely affect foreign investments.

“While many human rights issues are addressed in China’s labor laws, the grievance mechanism is not entirely victim-centered,” Zhang said, in large part because China’s dejudicialization efforts, in which courts are not the venue for resolving social, political or economic issues, have made grievance mechanisms more difficult to achieve. The promotion of dejudicialization does not align with the UNGP’s expectation that local governments impose legal obligations on private actors.

This is a ubiquitous problem for many developing countries where actors often lack the political will to challenge business elites and pursue transformative change. Zhang says, “Human rights abuse is not an isolated phenomenon. You might find similar situations in many other emerging economies, or even in some regions in the West.”

At the same time, workers are often unconscious about their rights or hesitate to seek legal justice. Can we expect civil society organizations like China Labor Watch to gain legitimacy from, as Zhang says, “the advocacy for workers’ rights in real, practical issues, empowering and inspiring workers to stand up for their rights and remaining hopeful even in a totalitarian regime”?

The UNGP’s expression of soft law can, hopefully, become more effective if civil society actively participates in human rights and development to add pressure on local governments to introduce legislation and policies regarding the three pillars introduced in the UNGP. Civil society activists could also play an increasingly representative role in helping workers in their knowledge and advocacy of their rights and justice. Lastly, civil society activists could constantly monitor business performance to ensure compliance with human rights-related regulations.

For countries with a totalitarian regime like China, however, the state represses civil society behaviour that might disrupt the central government’s development blueprint. But as Zhang says, “We hope to empower and inspire workers to stand up for their rights, and remain hopeful even in a totalitarian regime.”

The outlook

The UNGP provides guidance for the implementation of the “Protect, Respect and Remedy” framework, and offers advice to governments, businesses and civic organizations. The terms used in the UNGP reflects a division in the role of state actors and non-state actors regarding human rights. “Duty” is used specifically to highlight the obligation of states to comply with international law and to implement litigation processes that protect against human rights violations. “Responsibility” refers to corporate obligations in neither legal nor political terms, but as a relatively flexible moral commitment.

In general, business owners are not familiar with international human rights law or the Guiding Principles. People who have migrated from rural areas to engage in the urban job lottery with the hope of a better life tend to have minimal education. Their career aspirations are often limited to simple manufacturing. In the interviews, there was little indication that these rural-urban migrants understand the meaning of human rights and how to defend themselves from human rights violations.

Human rights due diligence requires an extensive information management system, with constant internal evaluation and public feedback tracking, and broader stakeholder involvement. According to Daolong, businesses often find human rights-related measures to be unprofitable and costly to maintain. Unless a company gets caught in a major human rights violation scandal, in the absence of an engaged civil society there is little incentive to adopt the due diligence required by the UNGP.

Perry

I admit that there are some human rights issues in China and some developing countries now, such as excessive working hours and bad working environment. In my opinion,this is due to the division of labor in the world’s industrial system.

For the developed countries they owned the core technology so that they can just do the R & D and determine the global strategic direction. But for the developing countries, due to lack of core technology, they can only join in the world industrial system through labor-intensive industries. For example, Apple in U.S only focuses on product development and system upgrade. This is an easy and highly profitable business. Apple’s production lines are all over the world,, especially in developing countries. They hire cheap local workers to do specific production work, this is the lowly profitable business. To be honest, if the countries that have technology don’t distribute more profits to these developing countries, business owners in developing countries will reduce costs by oppressing workers .This kind of human rights issues will always exist