The plight of Adivasi women in India is dire. Like countless Indigenous women around the world, many Adivasi women are at the forefront of the anti-extractivist struggle with the goal of protecting their land. Doing so, however, places them in a vulnerable position, as the political repression they face is often sexual in nature. Not only that, but many Adivasi women face additional discrimination and violence at the hands of their own community members.

“Witch-killing and witch-blaming are used as weapons, when not just single, weaker women are targeted but women who are very active at the community level or doing good for the broader community that are also targeted,” says Elina Horo of the Adivasi Women’s Network.

“There are different types of violence revolving around these lands and resources. I am also surprised that witch-killing and witch-blaming in different forms are still in practice in Jharkhand. Even witch-blaming is a big thing, because this stigmatizes women. It acts as a character assassination kind of thing. Apart from that is the killing – brutal killing – this kind of mob lynching undertaken by the whole community. This is one of the saddest parts of the discrimination experienced by Adivasi women”.

To better understand the challenges these women face, I spoke with four experts about what has been unfolding within Adivasi communities and on Adivasi land for decades now.

· A post-doctoral researcher, who asked to be unidentified, focusing on gender & dispossession.

· Signe Leth, Senior Advisor of Women & Land Rights, Asia at the Copenhagen-based NGO International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs (IWGIA), with a special focus on Indigenous women’s rights, Indigenous Peoples’ land rights, and human rights defenders.

· Elina K. Horo, renowned Adivasi activist, president of the Adivasi Women’s Network, author of “Decision- making process of Indigenous Peoples in Jharkhand (Chhotanagpur) and in Central East India”. Updates on her activity are here on Twitter.

· Jayshree Bajoria, author of the human rights report “Everyone Blames Me” about sexual assault in India, and senior researcher for Human Rights Watch based in London.

Who are the Adivasi women?

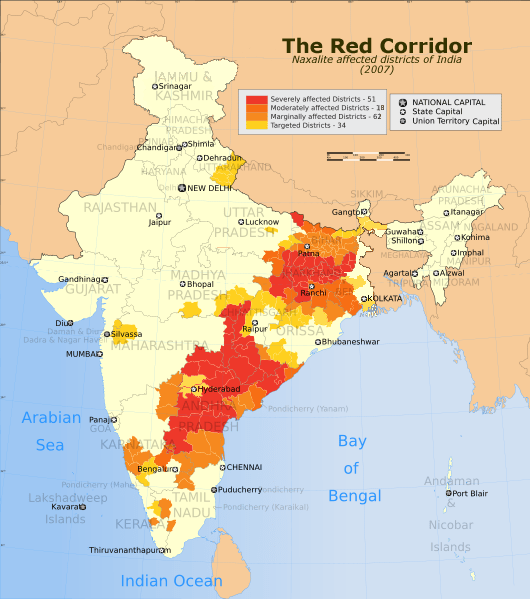

There are 104 million Adivasi people, according to Minority Rights Group International, making them the largest Indigenous community in the world. The term Adivasi signifies “earliest inhabitant”, and Adivasi people today are understood to be descendants of India’s first inhabitants. The term Adivasi also became an umbrella term to define those that live within India’s remote and rural areas, with the largest communities in states like Jharkhand, Andra Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Orissa, West Bengal, Rajasthan, and Bihar.

Many Adivasi communities still strongly rely on land- and forest-based subsistence for survival, which is why the ongoing land dispossession, undertaken in the name of Indian state development, affects these communities so deeply. Also, due to their geographical location, many Adivasi communities are removed from social and cultural influence, allowing the Indian government to engage in assimilationist actions.

Because of their relative geographical and cultural removal from mainstream Indian society, the general discourse regarding Adivasis in India tends to be extremely prejudicial, as other people understand them to be backward and primitive. This is why assimilationist projects, forced displacements and repression are not necessarily viewed in a negative light, and consequently spark less broad moral outrage when they do take place.

The academic source told me that it is important to underline that state projects focused on dispossession appear to be centered on a kind of violence that specifically targets Adivasi women.

“By targeting women there is an immediate sort of consequence, which is that their communities’ entire generation-based livelihood mechanisms are destroyed, or disrupted at least,” she said. “And this is not just about women, but also about the entire communities as such. Women become the center, because a lot of the life, the livelihood activities like agriculture and sustaining labour there, are obviously in the hands of women. And so that gets disrupted”.

The Naxalite insurgency

Signe Leth, Elina K. Horo, and the academic source agree that one reason why the land dispossession has been especially brutal and violent can be traced back to the fact that many Adivasi communities find themselves in the crossfire of another, ongoing state conflict, which pits Maoist insurgency groups, known as the Naxalites, and Indian state security forces. Often, this fight occurs on the same territory that has been inhabited by Adivasis for centuries. It is common for the Indian government forces to attack, imprison, and even kill Adivasis on the suspicion of sedition against the Indian state, or based on suspicion of membership within Maoist insurgency groups, even with little or no evidence.

For the academic source, this extra-legal violence is all part of the land dispossession project backed by the Indian state, because Adivasi lands are coveted due to their richness in minerals such as bauxite, coal, and iron ore. “A part of this dispossession has been to be violent against these communities because dispossession cannot be mutual and happy, go-lucky. And that is where you get to see violence in different forms.”

According to that person, many people in India are unaware of the tactics used in forced dispossessions. “It never really touches the urban population and their imaginations because it doesn’t directly concern them, is what I think. And the state narrative is very clear that, whatever is going on, it is legitimized,” she said.

When this violence relates to women, the academic source says, “It is sexual in nature and those doing it are the military forces, the police forces that have been deployed there to control the Maoist movement. They just set up camp whenever they like and will, on the basis of suspicion, attack anyone they like. Even if a woman is killed or raped, or suffers the custodial violence that goes on when women are arrested and imprisoned, it is in the name of countering the Maoist insurgency.”

Abuse of Adivasi Women as a Silencing Tactic

The use of repression tactics such as custodial violence and rape perpetrated by the military state forces and police targeting Adivasi women is not fortuitous. Such violent tactics are used because they instill fear in the women affected and also within the larger Adivasi communities.

Jayshree Bajoria explained how patriarchy and patriarchal ideologies are deeply embedded in the social fabric of society, so that a family’s honour lies with the women of the family.

“This notion of honour leads to this culture of silence. The woman herself is blamed,” she said. “There are the family members around them, the larger society that will put pressure on them to keep silent. There will be things like, you have younger sisters who have to get married, you have to get married. Stigma comes a lot from people around you, from family, from society, that acts as a deterrent to speaking out.”

Male members of the community can view an attack on the women as an attack on the community itself, the academic source says, so the community as a whole will be apprehensive about resisting land dispossession and the security force raids and attacks.

“The violence is therefore silencing not just those women who are actually rising up and speaking, or participating in protests, or getting legal access and whatnot, but it also helps to silence the community as a whole. And this is because you don’t want to lose your honour. You don’t want to lose the lives of the women of that community,” she says.

Evidently, the repression tactics centred on sexual violence do end up taking a toll on all Adivasi women. The knowledge that protesting will likely put a target on your back acts as a deterrent to resisting and speaking out against the ongoing human rights violations and infringement of Adivasi land protection laws, the academic source said. In this way, the targeting of women, and more specifically the tactics of sexual violence, can have the effect of rendering Adivasi communities more vulnerable to violent and illegitimate displacement and dispossession.

Adivasi Women and Patriarchal Ideologies

A common conception many have regarding Adivasi communities is that they are egalitarian havens, differing greatly from the rest of India which is generally stratified along caste and gender lines. Although there is some truth in this perception of Adivasi societies, as women in certain Adivasi communities do take on roles that appear to grant them greater agency and freedoms, it is nevertheless important to underline that within many Adivasi communities, patriarchal ideologies do exist and influence community members’ everyday decisions.

“There’s always this patriarchal notion with the land and who should own the land,” the academic source said. “And the state obviously supports that, not out of moral obligation or patriarchal obligation, but, because the laws are designed that way. It is more convenient for the states to interpret the land as masculine and belonging to a male owner than to a female owner.”

Community-Based Violence

Not only do Adivasi women face violence at the hands of police and security forces for speaking out brutal land dispossession tactics, but they also face violence at the hands of their fellow community members.

“There are harmful traditional practices in many of these indigenous communities”, Signe Leth says. “So, for instance, there’s a huge issue with witch hunting in many of these communities.” Importantly, Leth, the academic source and Horo say that those targeted by these witch hunts are, in the majority, women.

The notion of land ownership being owed to the male counterpart affects Adivasi women, and is a motivator in witch hunts, which have involved community expulsion or even mob lynching.

“Those people who are labelled as witches are hunted, and most of the time – there is data on this – these women who are hunted as witches are people who are landowning women. There are very, very few women who own land, not because they were powerful enough to take it, but mostly because the land-owning men in their family died, and there was probably no son to transfer it to. The land is therefore transferred to the women not by choice,” the academic source said. “Witch hunting functions as the dual purpose of enforcing the patriarchy within the communities, but also the Indian state, and of course contributes to the entire narrative of ‘Adivasis are not today’s people, so let’s get rid of them’.”

In terms of the process by which women come to be labelled as witches, Horo said that in many villages, when a member of someone’s family falls ill, instead of going to the hospital to see a doctor, they will visit a village healer instead. “If somebody dies or somebody gets sick, and they don’t know why, the family will not go to the doctor, because the health systems are very weak in India, and especially in Jharkhand,” she said.

Horo explained that the local healer may say “somebody is doing something bad to your family, and this person is sick because of this”. This kind of interpretation responds to the family’s desire to find a cause, but the blaming may be backed by other interests, and specifically used to target a woman of the community. “The witch hunt is now very politicized, in the way that it is used for various purposes,” Horo said. And one of these purposes revolves around the concept of land ownership, and who is rightfully and lawfully understood to have rights to land.

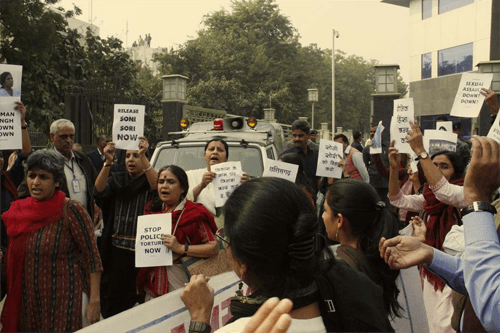

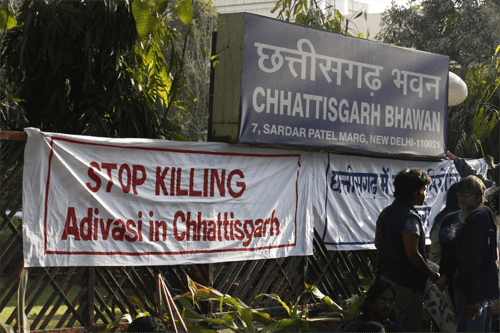

Photo: Joe Athialy

Leth and Horo specify that being a land-owning Adivasi woman is not the only reason why community violence in the form of witch hunts is orchestrated and targeted specifically at the women. Women who are perceived to be challenging patriarchal notions of women’s roles within their communities are also being targeted by community witch hunts.

“If a woman is too outspoken about women’s rights, entertaining an attitude that is seen to be a bit too powerful and that is challenging too many of the community’s practices, the community might just accuse her of being a witch, and simply chase her off, out of the community,” Leth said.

Exploitation of Adivasi Women

“With so much violence, and when you know that the violence is going to be sexual in nature, there’s been a tendency to migrate, migrate to nearby towns and cities”, the academic source said. However, once migrated to larger cities, Adivasi women are faced with different forms of abuse.

“Sometimes, because even that the migration to larger urban centers cannot provide you the kind of employment to sustain yourself, you end up getting into sex work, you end up getting in domestic work,” she said. “There are agencies that capitalize on that. There are sex work agencies, domestic work agencies that specifically look for these women, or young girls, because you can exploit them more easily, right? They are coming from such distraught conditions that they won’t negotiate, except for the amount they just need to survive.”

An added factor that contributes to their exploitability is their illegal status when they find themselves in these larger urban centers, the source said. “They are so-called illegal in those cities, because they don’t have documents, they don’t really have those documentary records which are required for citizenship in a particular state.”

“All these conditions, once combined, render Adivasi women vulnerable,” Leth said. “And there is the trafficking of indigenous girls, especially in domestic services, not just in northeast India, but everywhere in India, where girls are being sent off to work in more high caste and high-class homes under terrible conditions.”

Adivasi Women and Resistance

Although all odds are against Adivasi women, there are instances of resistance, regardless of the consequences. There are many activists that have gathered behind the plight of the Adivasis and Adivasi women specifically, including many Adivasi women themselves.

“There’s certainly been resistance. And resistance, again, is not something which is recent. It’s been there since the very beginning and has been ongoing since this whole process of dispossession started in the late 1800s,” the academic source said. “But things have been heightened because places like Chhattisgarh have been created. The violence has been heightened, so there is ongoing resistance, there is daily resistance in terms of them organizing as women collectives and as Adivasi collectives. Because when people die, or when women are raped, that evokes a lot of resistance at that point. And that has happened in the recent past quite a few times. Even just this last May, the police forces created a new camp in the area of Bastar, and the protests are still on.”

Chhattisgarh was the site in May 2021, when three Adivasi people were killed and several wounded by police during a protest. This followed violence a month earlier in the area, when twenty-two police were killed in conflicts with Naxalites.

Outside of this unfortunate violence, resistance can also take the form of inter- and intra- community solidarity networks aiming to empower Adivasi women.

“The Adivasi Women’s Network actually started first from my own experiences, being an Adivasi woman, we face kind of a discriminatory attitude in the workplace and the community,” Elina Horo said. “I realized that, when I had the experience of inquiring with other women also, that they were also facing different levels of discrimination because they are Adivasi. In that way, we started connecting ourselves to get more solidarity, support, moral support, and that was the beginning.”

She told me that finding that other women were also experiencing similar struggles was greatly motivating in trying to understand the root causes for such discrimination, and it pushed her to find strategies that would diminish Adivasi women’s chances of being exposed to such struggles and situations.

As she extended her network in a more grassroots manner to be more centered on Adivasi rural communities, she realized that both urban and rural Adivasi women faced discrimination and abuse. Incidents such as domestic violence, witch hunts, and other forms of sexual violence were reported by rural Adivasi community women.

“Those were the connecting points for us,” Horo said. “By being a woman, being an Adivasi woman, we have the same experiences; though there are different categories of women, some single women, married, and also some disabled women, there was one commonality, being Indigenous women. So we got connected with each other. We started with a slogan – “Empowering women is empowering our community.”

The network expanded into a much larger operation once it sought to raise funds to back their projects.

“Slowly, we started to holistically empower women, socially, economically and politically. Through various activities such as leadership training, capacity building, skills training, advocacy training, and so like that women got some space and men, traditional leaders, they became gender sensitive a bit. But it is still a hard, patriarchal structure, you know, and to change the mentality, it will take years, but we are still trying.”