Human rights and environmental protection – are they adequately ensured when the World Bank does its buying? This article explores the intersection of the World Bank’s procurement standards and its environmental and social safeguard policies.

In 2014 the World Bank investigated a project in which Sengwer indigenous people of Kenya were forcibly displaced from their homes and their communities burned down. It found that the involvement of the Bank in this disaster to be in violation of its social safeguard policies. This was just one example of the problems with World Bank standards to prevent social harm in its projects.

Recently, following a fiercely debated process, the Bank harmonized its social and environmental policies into one set of safeguards; its new Environmental and Social Framework came into effect in October 2018.

Are they sufficient? Do you extend to all aspects of World Bank operations?

One area that escapes scrutiny is the World Bank’s procurement process, and whether it ensures that the materials and services that are being contracted, and the means and methods by which they are being procured in these projects, are ethical, safe, and respectful of human rights and the environment.

The world’s biggest marketplace – public procurement

At US$9.5 trillion per year, public procurement is what the World Bank calls “the world’s largest marketplace.” Developing countries spend $820 billion each year purchasing goods and services from the private sector. The World Bank’s procurement team now supports over 1,750 active projects and around 480 projects in preparation, with staff in 72 countries. The Procurement Framework web page states that the team works with governments “to achieve the highest bidding and contract management standards to get the best development result.”

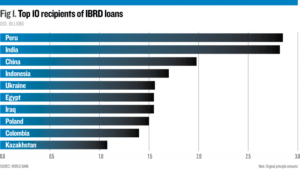

Geetanjali Chopra, communications advisor at the Operations Policy and Country Services Vice Presidency at the World Bank Group, explained to me the role and scope of the main institutions in the World Bank Group that manage this procurement, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) and International Development Association (IDA). IBRD is the largest development bank in the world, providing loans, guarantees, risk management products and advisory services to middle-income and creditworthy low-income countries. IDA is one of the largest sources of assistance for 76 of the world’s poorest countries, providing concessional loans and grants for various programs and “is the single largest source of donor funds for basic social services in these countries.”

Together, these agencies champion Investment Project Financing (IPF) which, Chopra said, is “used in all sectors, with a concentration in the infrastructure, human development, agriculture, and public administration sectors.” IPF not only focuses on commercial lending but also supports borrowing countries by “supplying them with needed financing and also serving as a vehicle for sustained, global knowledge transfer and technical assistance.” IPF is a significant area of finance for the World Bank – in 2012, out of the entire Bank portfolio, investment finance represented 82% of the Bank’s projects and 65% of its financial commitments.

As the web site of the World Bank Group says, the missions of the IDA and the IBRD, along with its other agencies, “share a commitment to reducing poverty, increasing shared prosperity, and promoting sustainable development,” with their collective reach representing a force that is vastly influential, extensive and profound. The World Bank now has a portfolio of more than 12,000 development projects, with IDA and IBRD providing loans and grants of US$45.1 billion in 2019.

Money well spent?

Although this financing may be best-intentioned and aimed at uplifting communities around the world “sustainably,” there is a constant need to critically examine the gaps that may still persist between theory and policy prescriptions and actual implementation and practice.

Carl Söderbergh, director of policy & communications at a UK-based NGO, Minority Rights Group, emphasizes that holding these global establishments to account is important, especially when dealing with such huge levels of IPF in the largest marketplace. “I think it’s important to emphasize how incredibly powerful they are,” he wrote in our email correspondence. “They’re going in and funding huge infrastructure projects that can affect populations of tens and hundreds of thousands of people. And we have just seen disasters happen where the World Bank is not holding the governments to account and is funding violations of human rights to a really egregious level.”

There is a complex bureaucratic process that comes along with World Bank IPF, but this does not mean that it is exempt from continuous evaluation and a guaranteed respect for human rights at all levels should not be allowed to get lost in the fog of intricacy.

The world has seen hallmark international agreements and treaties signed such as the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (2011) and a growing business model centered on the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) form the basis of our normative global order and behavior. Therefore, it should logically follow that the World Bank, as a global, publicly-funded agency with massive influence should be representative of these ideals. Its investment project financing and public procurement are, according to Enzo de Laurentiis, the Chief Procurement Officer at the World Bank, accounts for at least 15% of GDP in many developing countries.

Environmental and social protection – the World Bank’s new policy

The World Bank’s Environmental and Social Framework (ESF) was the product of an extensive four-year drafting process that included wide participation of concerned stakeholders. It began with preliminary consultations in October 2012 and was concluded in August 2016 with the approval of a final text. This text aimed to comprehensively update its former and largely insufficient ‘safeguard policies’ which had only received periodic and piecemeal revision since 1997. The new Framework covers ten areas of environmental and social standards, covering issues of cultural heritage and indigenous peoples, stakeholder engagement, land acquisition and involuntary resettlement and the conduct of environmental and social impact assessments. It applies to all Bank IPF as of October 1, 2018.

“This Framework enables the World Bank and Borrowers to better manage environmental and social risks of projects and to improve development outcomes,” Chopra said. It does this by offering broad and systematic coverage of environmental and social risks, she said. “It makes important advances in areas such as transparency, non-discrimination, public participation and accountability. This brings the World Bank’s environmental and social protections into closer harmony with those of other development institutions. Its architecture provides better clarity on the different roles and responsibilities of the World Bank and the Borrower.”

Moreover, Chopra argues that the scope of social issues addressed has been expanded, while “enhancing requirements for transparency and stakeholder engagement, expanding requirements for grievance redress mechanisms, and including non-discrimination provisions to protect disadvantaged or vulnerable individuals or groups and to allow them to access the benefits of the project.”

“The ESF requires Borrowers to consider project-related transboundary and global risks and impacts, such as climate change mitigation, adaptation and resilience issues,” she says, arguing that it promotes adaptive management of environmental and social risks and impacts.

Limited progress

For another opinion on whether the new framework represented a progressive step forward, I contacted Corinne Lewis, a prominent lawyer and human rights advocate for Lex Justi, a legal consulting firm based in Brussels. As its web site indicates, Dr. Lewis has carried out policy and advocacy work on a range of topics, including supply chains, infrastructure projects, social and environmental standards and compliance mechanisms for international financial institutions.

“In terms of progress, it definitely is. I think there is no question about that,” she said. “Is it as far of a step forward as many NGOs would like, as I would like? No. But, it is an integrated framework that replaces sort of a patchwork set of policies that the World Bank had, and creates a document that is made up by the framework and the accompanying guidance notes. Not only is it integrated, but it’s also a much more comprehensive framework, covering topics that weren’t included at all in safeguard policies before.”

In terms of explicitly addressing human rights in the ESF, Chopra noted that the framework emphasizes, in its aspirational vision statement, that World Bank activities support the realization of human rights expressed in the UN Declaration of Human Rights. She said that the World Bank, in a manner consistent with its by-laws, will continue to support its member countries as they strive to achieve their human rights commitments. However, those by-laws (called the Articles of Agreement) do not refer to human rights.

Lewis and Söderbergh are both authors of The World Bank’s new Environmental and Social Framework: some progress but many gaps regarding the rights of indigenous peoples (International Journal of Human Rights, May 2019). They say that, despite the statement of aspiration on human rights, there is a fundamental problem embedded within the Framework itself. “The Bank’s lack of an express obligation to respect human rights and to promote respect for human rights by borrowers receiving investment financing from the Bank.”

The “politics” of human rights

Söderbergh took part in the consultative process on the ESF. “It was almost comic actually. The World Bank was really hesitant even to mention human rights at all,” he said. “The officials were saying something like, ‘human rights, they’re political, they’re difficult, this isn’t our area.’ And we and donor governments were saying ‘but you’re a U.N. Agency and the whole of U.N. is meant to promote respect for human rights. Why aren’t you stepping up?’ And the final outcome, the language is something like ‘the World Bank’s activities will support the realization of human rights.’ We were relieved to see that, but we just thought it was a little odd that even that language feels very passive. Why not just go ahead and say that the World Bank will promote respect for human rights?”

For Söderbergh, this is a fundamental misunderstanding of human rights and states obligations to human rights treaties. He and Lewis consider the World Bank’s ESF to be emblematic of a risk-management approach rather human rights-based approach. The Bank’s main role under this risk-management approach can then be seen as one of preventing, mitigating, and minimizing undue harm and risks, but with a notable lack of active promotion of human rights.

This weakness can be seen clearly in the Framework’s loose language. For example, if a project that a borrower is going to carry out doesn’t meet the ten ESF standards at the time of the Bank’s approval of the project, it only requires the borrower to take steps to meet them “in a time frame that’s acceptable to the Bank.”

“The Framework incorporates key human rights principles, including transparency, accountability, consultation, participation, non-discrimination, and social inclusion,” Chopra said, although in practice it appears that responsibility for these aspects can be shifted from the World Bank to borrower governments.

My editor at the Upstream Journal, Derek MacCuish, was heavily engaged in the consultation process leading to the ESF, taking part in four years of discussions in Washington and Ottawa. He agrees with Söderbergh and Lewis that the key element was the desire for risk aversion.

“The team preparing the policy included people who were in favour of human rights requirements, but also a person from the legal department who was stubborn on the issue of human rights. He didn’t want any reference to international human rights law,” MacCuish said. “Local and national law was fine, and it was safe to refer to the UN Declaration on Human Rights, which is aspirational and, unlike UN agreements on rights of the child, of women, of indigenous people, of people with disabilities et cetera, has no actual legal requirement.” MacCuish believes that the purpose was to protect the World Bank from liability.

Another dynamic, he says, is that only a few members of the board of directors were willing to argue for strong human rights standards. Countries like China, India, Brazil, Russia and most African and Middle East countries, for example, were opposed to various aspects of human rights requirements. “It was a perfect storm of opposition to human rights obligations,” MacCuish said. “What emerged is the best we could hope for.”

The safeguard policy in practice

In order to meaningful apply this ESF policy, the Bank commits itself to undertake its own due diligence of proposed projects “proportionate to the nature and potential significance of the environmental and social risks and impacts related to the project” and, “where required,” to support the borrower in conducting effective early and continuous engagement and consultation with relevant stakeholders, and providing adequate grievance mechanisms.

Chopra sees this call for proportionality as key. “All risks should not be treated equal, and more resources should be allocated to projects with greater risks,” she said. The ESF then continues to lay out specific Environmental and Social Standards (ESSs) that are, “designed to avoid, minimize, reduce or mitigate the adverse environmental and social risks and impacts of projects.”

Again, the language is grounded in risk-management while human-rights based principles are notably absent, although Chopra drew my attention to new mandatory World Bank directives, “Addressing Risks and Impacts on Disadvantaged or Vulnerable Individuals or Groups” and “Environmental and Social Directive for Investment Project Financing” which “requires staff to assist borrower governments to consider, mitigate, and manage potential impacts on such individuals and groups.”

What it means in procurement contracts

How does this ESF translate to World Bank procurement policy then? Lewis said that in essence, procurement is the World Bank providing money to governments, and those governments then providing money to purchase the services of businesses that are going to construct a project. A chain of suppliers is then formed in this procurement of goods and services with the financial backing by World Bank investment.

A section of the ESF, “Scope of Application,” asserts that “this Policy and the ESSs apply to all projects supported by the Bank through Investment Project Financing.” Thus, by attaching this ESF to IPF, the Bank and the borrower are mutually responsible for ensuring that environmental and social standards are met throughout the project.

The Bank’s obligations are laid out in the first section of the Framework, called the Environmental and Social Policy for Investment Project Financing. It states, “The Bank is committed to supporting Borrowers in the development and implementation of projects that are environmentally and social sustainable, and to enhancing the capacity of Borrowers’ environmental and social frameworks to assess and manage the environmental and social risks and impacts of projects.”

The broader and hotly debated question is raised after examining all this of how, whether, and to what extent do you hold a bank responsible for the conduct of businesses to which it is supplying the finance? “Responsibility for violations of human rights by businesses in a company’s supply chain remains an open issue within the business and human rights field,” Lewis says. “In terms of legal responsibility, this is a very gray area.”

The U.N. Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights outline that the importance of a process in which due diligence is continually conducted. Essentially, Lewis says, “You’re supposed to be ensuring that you’re determining where the risks are in your supply chain and targeting the most severe risks and taking action. But to what extent is the World Bank held accountable for that? That’s unclear.”

If looking at the first ESS in the ESF, centered on assessment and management of environmental and social risks and impacts, paragraph 34 provides that the borrower is supposed to conduct an environmental and social assessment and in doing so, it has to consider risks and impacts that are associated with the primary suppliers. However, it continues, further narrowing the level of responsibility of the borrower holds towards its primary suppliers, by stating that, “the Borrower will address such risks and impacts in a manner proportionate to the Borrower’s control or influence over its primary suppliers as set out in ESS2 and ESS6”. ESS2 relates to labor and working conditions and ESS6 relates to biodiversity conservation and sustainable management of natural resources.

This language of control or influence is inconsistent with the UN Guiding Principles, which is based on the idea of relationship, and ends up allowing for the limiting of borrower responsibility over impacts in their procurement supply chain. Even the definition of primary suppliers in the footnote limits this supply chain responsibility further by categorizing them as, “those suppliers who, on an ongoing basis, provide directly to the project goods or materials essential for the core functions of the project.” Who then exactly decides which materials to classify as ‘essential’ and what exactly the ‘core functions of the project’ constitute?

It is in these minute details in terminology and passive rhetoric that many civil society actors, including Lewis and Söderbergh, found issue during the years of drafting and consultation, and remain apprehensive about today. Lewis finds these “definitions extremely limiting” and see it as problematically allowing for a “cascading of narrowing responsibility on the borrower and the Bank.”

“International financial institutions and banks can have an influence on businesses if they are requiring businesses to meet the UN Guiding Principles. They can encourage greater respect for human rights. So, by having this sort of limited definition of responsibility you make this very narrow and, in that sense, it’s not really consistent with the direction in which the business and human rights field is moving.”

Söderbergh says that that, throughout the drafting process, “It was admirable on the one hand that there was this really strong and extensive commitment to consultation. But one can question how serious that consultation is when so much is at a technical level. You know, what are you demanding of civil society activists, and indeed governments, when you’re presenting delegates with documents of such extraordinary levels of complexity?”

It is in this complexity that Söderbergh expresses worry about the possibility of holding the World Bank officials to account in varying local contexts. Much of the responsibility ultimately falls on the shoulders of civil society actors, specifically NGOs, saying, “A lot of us are small NGOs, and lack the kind of reach in order to monitor systematically, and ensure that the local communities that are concerned know about these ESSs and know the level of detail in order to pursue complaints.”

The next evolution of responsibility

Overall, Lewis sees this as perhaps signalling a broader crisis in the model of sustainable development investment and lending, with not only the World Bank but also several regional financial institutions offering lax requirements on borrowers to ensure human rights and environmental protections in their procurement processes.

“I think in that sense, it’s helpful to look at it as a more global problem of leading international financial institutions providing development assistance,”she said. “We need to look at the fact that okay, we’re promoting development. But who are we promoting development for and what are the costs? And in order really to have a change and to have the World Bank perhaps promote these policies with its powers, the way it should work to protect the environment and promote and ensure respect for human rights of communities, there needs to be just a refocus and rethinking in terms of how we approach development projects.”

The Bank, in its evolution and growth, is caught up in a system that promotes furthering development but always at a cost, she says. Lewis believes that the environmental and social costs haven’t been adequately accounted for. “The field is moving in the right direction, but there’s a lot of work that needs to be done,” she says.

Söderbergh echoes these sentiments in his belief that, “Fundamentally, it’s about ensuring that all development actors bring a human rights-based approach to economic development.” He sees the solution in the active promotion of the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). He sees the intersection of the World Bank’s ESF and procurement policy, and its ultimate responsibility as a hugely powerful investor and lender, will remain contentious until it is willing to include, explicitly, U.N. promoted human rights-based language and a following approach to its policy, implementation, and practice.

“I see the SDGs as a kind of 360 framework of development, including issues to do with the environment and also equality and human rights. And so, we can also use the SDG’s framework, and the fora that have been developed around the SDGs, as ways of arguing for human rights. The World Bank is situated right there as a hugely important actor in that space. So we need to use the SDGs in order to get them to do the right thing.”