Click here to hear the companion podcast

“Kill me now, please kill me.” This was how Basema, a middle-aged Yazidi woman now living in Toronto, recalled her harrowing experience of being abducted by ISIS, separated from her family, and sexually assaulted during the Yazidi genocide in 2014.

The genocide

On August 3rd, 2014, ISIS militants launched a brutal attack against the Yazidis, an ethno-religious minority, in Sinjar, a region in northern Iraq. For centuries, the Yazidi people have been persecuted, in part because of their religion which has been misrepresented by many, including ISIS, as one of devil worship. Basema and her family were among the thousands targeted.

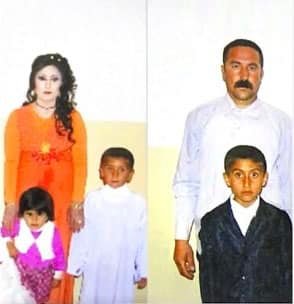

When the militants invaded Sinjar, they separated men from women and children. Yazidi men and elderly Yazidi women were killed immediately. Basema’s husband was one of them. Young Yazidi boys were forced to convert to Islam and fight for ISIS, while girls and women were used as sexual slaves. Basema’s four-year-old daughter was abducted, and soon after, her 11-year-old son was taken to be trained as an ISIS fighter. Alongside many other Yazidis, Basema and her remaining son, just 7-years-old, were transported to Raqqa, Syria, where they lived under constant surveillance and control.

There, Basema was sexually assaulted by an ISIS member for the first time as she pleaded to be killed. Rather than fulfilling her request, they condemned her to live.

Two years later, Basema began to plan her escape. With the help of a Muslim woman connected to ISIS and motivated by Basema’s father’s money, Basema was able to confirm that her parents were still alive and living in Sinjar. Basema then asked that her older son be allowed to visit her and her younger son at the house where they were cooking for ISIS fighters. Claiming she was ill and needing to see him, Basema convinced an ISIS member to grant her eldest son a two-day visit.

With the opportunity this provided, she and her sons tiptoed out of the house at dawn and hailed the first taxi they saw. They remained in the car until Basema spotted a man smoking a cigarette. Since smoking is considered haram (forbidden) by ISIS, Basema knew that he was not an ISIS member. They got out of the taxi, and after some convincing – and in return for a sum of money that Basema’s father collected in their village Kocho in the Sinjar district – the man reluctantly agreed to shelter her and her children.

Before long, Basema and her sons set off on foot toward Kobani, a Kurdish-majority city in Syria, 135 kilometres away. For three days, they walked without food, water, or sleep. Basema and her sons were close to Kobani when she met someone who spoke Kurdish, her native language, and he drove them the rest of the way. After regaining their strength, Basema and her sons returned to Kocho, where Basema discovered that her daughter had also been returned to the village. It was the first time she had seen her daughter in two years.

On July 17th, 2017, Basema and her three children resettled in Toronto, Canada, with the help of the International Organization for Migration.

In this regard, Basema was one of the lucky ones. During the genocide, approximately 350 000 Yazidis were displaced. Some remain in refugee camps. Between 130 000 and 150 000 have returned to Sinjar, yet they face severe challenges, including limited access to education, healthcare, stable electricity, clean water, and the overwhelming psychological burden of their experiences. More than 200 000 remain trapped in camps for displaced persons, and another estimated 2 700 Yazidis remain missing and presumed dead.

The Role of the international community

NGOs have tried to step in to support the recovery of the Yazidi community and the Sinjar region. However, given the scope of the need and the limited resources available to NGOs, there has been little success. Rev. Majed El-Shafie, founder of One Free World International, a human rights organization based in Toronto, has [1] [2] voiced skepticism about the effectiveness of aid distribution, describing tangible improvements on the ground as limited. He suggests that systemic challenges, including informal markets, may be affecting the flow and impact of assistance.

Murad Ismael, co-founder and president of the Sinjar Academy in northern Iraq, told me that NGOs have largely withdrawn from Iraq in general due to broader shifts in global funding priorities, including reductions in support from agencies like USAID. As a result, less financial aid is being funneled through international organizations.

The lack of the international community’s involvement extends further than the aid cutbacks. According to Ismael, evolving international migration policies – particularly following Trump’s ascension to power – have impacted opportunities for Yazidis to seek refuge abroad. While some had begun the process of resettlement, those pathways have now been paused, leaving many Yazidis struggling for basic necessities in Sinjar.

Other geopolitical factors in Sinjar, including the presence of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party and the Iran-backed Popular Mobilization Force, and Turkish air strikes, have hindered efforts to stabilize the region and facilitate the voluntary return of IDPs.

Moreover, accountability for crimes committed during the genocide is limited. While the UN’s Investigative Team to Promote Accountability for Crimes Committed by Da’esh (as ISIS is also called) became involved, its mandate ended in 2024.

The Role of the Iraqi government

Despite ongoing challenges, the Iraqi government has taken initial steps to address the aftermath of the genocide, most notably through the introduction of the Yazidi Female Survivors’ Law in March 2021. This legislation created a system of reparations for, and recognition of, the survivors. However, there is concern that the implementation remains faulty and inconsistent, making the reconstruction of the Yazidi homeland a continuous social justice issue today, eleven years after the genocide.

Ismael explained that, while there have been rescue efforts, a comprehensive and coordinated program to bring home the estimated 2 700 Yazidis in captivity does not exist in the Iraqi government. He said that the paperwork process that was supposed to ease the return of the Yazidis has been halted because of political issues between Baghdad and Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan.

Rev. El-Shafie echoed these concerns regarding aid distribution and the slow pace of resettlement. He stressed the urgency of transforming the legislative progress into tangible change in Sinjar. As he put it, “You want to tell me, after ten years of the war, the Iraqi government is unable to resettle them back again to their home in the Sinjar mountains and elsewhere? You know, it’s horrible, it’s horrible. So the Iraqi government can pass whatever laws that they want, but with all due respect, their corruption, their lack of action, it is very, very clear that their desire to help does not exist.”

In 2025, the Iraqi government passed a General Amnesty Law granting freedom to thousands of prisoners, beginning with more than 19 000 released in May. There are concerns that this amnesty includes some ISIS members who helped commit the Yazidi genocide.