How an age-old practice can be turned around by educating local women

Female genital mutilation: local circumciser

I was born in Khartoum, Sudan, and lived there until the age of nine. I was born into a modern family – my father received his education in Europe – so my sisters and I escaped a terrible ritual that many other girls have to endure. Female genital mutilation (FGM), a practice that no one dares to question or defy, remains a taboo subject even though all Sudanese people acknowledge its existence.

I remember going with my mother to celebrate a big event for one of my friends. We were seven years old. I recall being surprised that she spent the whole evening lying in bed covered with crisp white sheets and did not seem to enjoy the festivity at all. I asked my mother what was wrong with my friend but I did not get an answer. It seemed that this was something that only grown ups could talk about, so I forgot about my friend’s behaviour and enjoyed the rest of the evening. Later on, I realized that I had been to a khitan party. In Sudan Khitan is a common word for FGM.

An old custom, primarily practiced in Africa, the procedure consists of the removal of some or all parts of the external female genitalia. This practice is still very common within Sudanese society. It is first and foremost a cultural tradition and it is not, despite what many claim, a religious requirement. Khitan is performed on girls between the ages of three and thirteen. It is considered to be a big event in a girl’s life, often accompanied by a celebration and gifts.

When I visited Sudan earlier this year, I was curious to know if this cruel practice still has a place in Sudanese society. (My family was forced to leave Sudan after the 1991 coup d’etat and came to Canada.) To begin, I met with Amira Elfadil, the Secretary General of the National Council for Child Welfare.

“I am against female genital mutilation, the National Council for Child Welfare (NCCW) is against female genital mutilation, and so is the government of Sudan,” she told me, adding that the NCCW council is mandated by the state to protect any violation carried out against children, and considers FGM to be a breech of the rights of children and women. Lack of education about the dangers of this practice is one of the main reasons why this dangerous practice still has its place in Sudan, she said. People who force genital mutilation on their daughters are often unaware of the side effects and the dangers that this practice may cause.

To begin with, FGM is not performed by medical staff. It is generally carried out – without anesthesia – by traditional excisors, old women who specialize in FGM, mainly in rural areas. Their instruments are not always disinfected, and there is no medical supervision.

Many people believe that it will reduce sexual desires and protect young women from corruption associated with sexual activity. Some rationalize the practice as an Islamic tradition, but Elfadil said that this is incorrect because within Islam only men are to be circumcised.

“Education plays an important role in decreasing this practice because it raises awareness and enables people to resist practices that work against social development,” she said. She considers it crucial to educate women and men in rural areas who are unaware of the dangers of FGM, and works with numerous women’s groups conducting educational campaigns about genital mutilation and its consequences.

The Sudanese Health Ministry has outlawed the practice, and has the authority to revoke medical licenses of doctors performing FGM. Parents, excisors or others involved in an FGM ritual could also be persecuted, but in practice the laws are limited since girls dare not accuse their parents or doctors.

The Ministry of Social Welfare and the Ministry of Women and Child Affairs joined several Sudanese non-governmental organizations to promote education about this issue, and some universities train students to go to rural areas and teach women about their health, their rights, and how to manage their meager incomes. One of the most important issues that they cover is female genital mutilation.

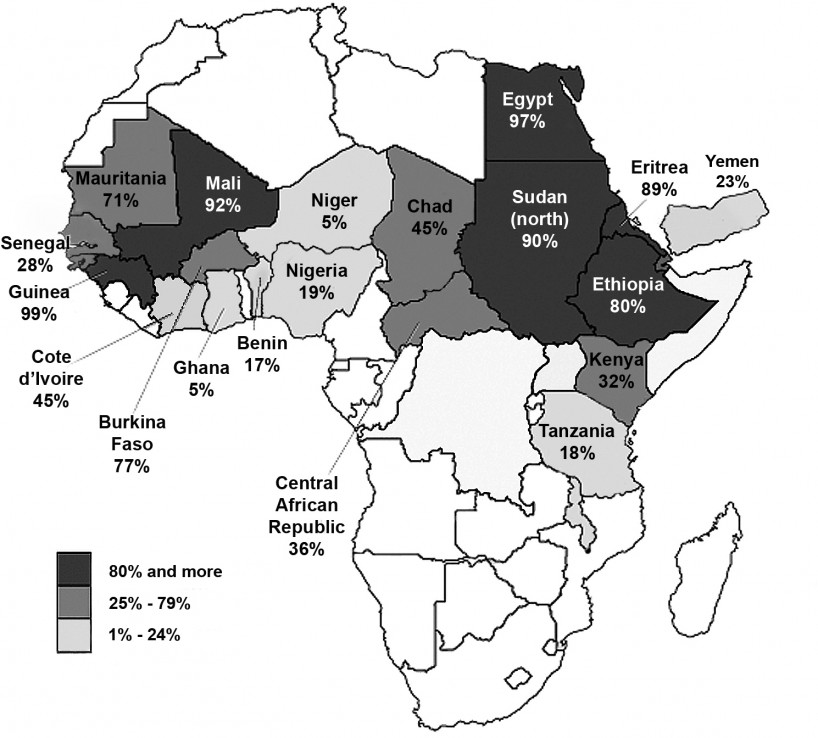

Eglal Mohildin works at Ahfad University, a private university for women situated in Omdurman, and is the Project Coordinator of the Regional Campaign for the Abandonment of FGM in Sub-Saharan Africa and Egypt. Motivated by her belief that women have the right to security in their sexual life, she is concerned that women in rural areas with little or no education continue to be governed by old traditions and customs.

“According to what I have witnessed while visiting rural areas, it is women themselves who are the reason why this practice continues in Sudanese culture,” she said. “When we ask mothers why they insist on having their daughters go through this procedure, they respond by saying ‘because that is how it was for us, for our mothers, for our grandmothers, and all our ancestors.” They fear that their daughters will become sexually active before marriage, not find men to marry them, and bring shame to their families.

“Our main goal is to convince mothers that this practice has more disadvantages than advantages, and that if they provide religious guidance and good values to their daughters from childhood, their daughters will grow up to be fine and pious ladies,” she said.

The students also inform the women about the dangers and side effects of this practice, which include serious infections, HIV, abscesses and small benign tumours, hemorrhages, shock, and clitoral cysts. Potential long term effects include kidney stones, sterility, sexual dysfunction, depression, urinary tract infections, various gynecological and obstetric problems and, in some cases, death.

Some of the women they visited in the past have taken their advice and decided not to inflict genital mutilation on their daughters. Unfortunately, these women can also become subject to ridicule and not well regarded by their community.

Even so, Mohildin remains positive. “We have hopes that if one woman decides to put an end to this practice, eventually others will follow,” she said.