Listen to the companion podcast here

More than one million Muslim Uyghurs are in Chinese internment camps. Why? What has been happening, and what will be the outcomes? I discussed the situation with three experts:

Darren Byler is a postdoctoral researcher with the China Made project at the University of Colorado, Boulder. His research focuses on Uyghur dispossession, culture work and “terror capitalism” in the city of Ürümchi, the capital of Chinese Central Asia (Xinjiang).

Barbara Kelemen, a China-Middle East security analyst, is a research fellow at the Central European Institute of Asian Studies and a research associate for Asia Pacific, Intelligence & Analysis at Risk Advisory Group, in London, England.

Julie Millsap is the Director of Public Affairs and Advocacy with Campaign for Uyghurs, in San Antonio, Texas.

Uyghurs in Context

As the situation in Northwestern China’s Xinjiang province deteriorates, the plight of Muslim Uyghurs, more than one million of whom have been kept in internment camps, has increasingly attracted media attention as well as legislative action on the part of various foreign governments. The Uyghurs are the largest Turkic ethnic group residing in Xinjiang, with the majority of the population adhering to the Islamic faith. The Uyghur political agenda is far from unanimous – some, generally the more violent sovereigntist groups, lay claim to an independent Uyghur state, whereas others seek to conserve an autonomous relationship with the Chinese government while maintaining a recognized distinct cultural identity.

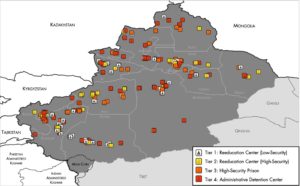

Uyghurs have become the target of a robust state programme targeted at suppressing nationalist uprisings that have been linked to incidents of domestic terrorism in China. The Chinese government considers the Islamic faith and nationalist sentiment to be chief obstacles to Uyghur assimilation; the internment camps, which have been euphemistically termed “re-education facilities” or “vocational education and training centers,” are spaces in which Uyghurs are subject to intensive indoctrination and compulsory religious deconversion.

Uyghurs are not the only Muslim-majority ethnoreligious group in China. The Hui – who like the Uyghurs are one of China’s 56 ethnic minority groups – are also adherents to Islam yet are not subject to the same regime of state repression. Darren Byler outlines three major reasons for the targeting of Uyghurs by the Chinese state: “It’s the fact that they speak their own language as their first language, that they have an ancestral claim to a large space of land, and that they are a large population as well, which is a significant factor.”

Byler also notes that there are clear differences in phenotypic traits between Uyghurs and the Han Chinese majority, which further contributes to their otherness. “They look different from Han people, and they can’t pass as Han. Those are all components which make them, in the kind of popular discourse deployed in China, a ‘hard’ minority rather than a soft one.”

Some of China’s smaller ethnic groups, who often speak Mandarin and can pass as ethnically Han, might be considered to be contributing to the diversity of China’s cultural sphere or as proof of China’s rich history. The same cannot be said of Uyghurs, Byler says. “They and the Tibetans, and to some extent the Mongols, are seen as most threatening to the unity of the nation to the stability of the nation. The other minorities are often smaller, so they’re more assimilated and in some ways are more malleable.”

Government Crackdowns

The Xinjiang internment camps have been operational since 2017 and can be situated within a broader policy, the “Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism” implemented by the Chinese government in 2014. Since then, China has utilized discourse on the Global War on Terror, launched by the US following the 911 attack in 2001, as means of legitimizing its efforts to contain domestic insurgency in the Xinjiang province.

Does China’s anti-terrorism program, employed as a means of quashing separatist sentiment, justify the camps, or is that a façade to assuage concerns over human rights? Barbara Kelemen says that it is a question of legitimacy. “Before any counter-terrorist measures can be considered, including mandating people to rehabilitation centres, you must define the basis upon which those people are suspected of carrying out attacks or being radicalized,” she said. “Based on the documents that are now available, if we examine the ways in which Chinese authorities are choosing these people, under no standards would they ever meet a bar of legitimacy.”

Kelemen also points out that there is reasonable debate over the aims of the internment camps. “There is a kind of divergence of opinions on whether China is actually trying to erase religion, or a completely separate ethnic identity. Are they trying to create a unified identity that is present in the whole of China?”

Byler stresses that the camps are indeed prison-like confinements: “Everyone knows that they are kind of carceral space, that they are a space of punishment.” Documents submitted by the Chinese government to the UN claim that the internees are akin to low-level criminals and that the extent of their criminality does not rise to a level at which they would need to be tried and sent to prison, but the decision as to who is sent to these camps is often made on the basis of religious conduct. “If you’re being sent to a camp for normative Islamic practice, then there’s a clear sense that this is not something that falls within a legal framework. This is an extra-legal, extra-judicial detention that explicitly targeting people based on their ethnicity and their religion.” He said that the internment programs are thus part of a discriminatory agenda. “It’s a form of institutionalized Islamophobia and racial profiling or ethno-racial profiling. In that sense, it’s quite abhorrent.”

There is reason to assume that the internment camps in China are related to the country’s current expansionist development projects, including the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013 with the stated objective of promoting regional multilateral cooperation in the Eurasian space, while advancing China’s geopolitical and geostrategic interests in Eurasia and beyond. The country’s agenda of economic growth and multilateral cooperation is carried out in conjunction with an ideology of peaceful rise and development explicitly designed to assuage foreign concerns about ‘the China threat’ while expanding its influence and economic power.

When asked about potential links between the internment camps and the Belt and Road Initiative, Kelemen said that Xinjiang does have a significant measure of relevance to the BRI in that Chinese authorities are heavily invested in the narrative that economic prosperity could foster international security, peace and exchange. The Xinjiang province represents a key gateway region in the BRI expansion project, and the threat of a Uyghur separatist uprising generates cause for concern over its smooth implementation, she said. “I suspect that Chinese authorities saw this economic development as a way to also address the issue of safety.”

Foreign Policy Responses

In response to the situation in Xinjiang, various foreign governments have either released statements condemning the China’s treatment of its Uyghur minority or passed legislation imposing sanctions and limiting engagement with Chinese industries. In 2019 and 2020 the US Congress passed a series of acts to respond to human rights concerns with support from both parties. When I asked her if legislation aimed at addressing the situation in Xinjiang might be driven by ulterior political motives, Julie Millsap said that it was unlikely to be motivated by partisan politics, but may be indicative of a shift in US policy concerns. “There’s been an increased awareness, even in the last few years, about how the US approach to China and policies is, in a lot of ways, quite outdated and naïve. Particularly under Xi Jinping, there is a need for a significant shift in terms of China policy.”

The Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act is the next step is a series of legislative acts aimed at curtailing human rights abuses in Xinjiang. These are targeted at a broad range of actors, notably industries and corporations that rely on forced Uyghur labour for their manufacturing activities. Referring to such companies, Byler describes some of the potential implications of this and similar legislation. “That will mean that they’ll need to reconfigure their supply chains or who they supply to. In the future I think we’ll probably see that work that involves Uyghur labor will be directed more towards the domestic economy in China, because they understand that people outside of China don’t want to buy those products.”

There is still more to be done, Millsap says, giving the Olympic Games as an example. “It’s really quite preposterous that a regime that’s committing acts of genocide is hosting the Olympics for the second time.”

Perhaps surprisingly, many Muslim-majority nations have not responded to the human rights abuses perpetrated against Uyghurs by the Chinese state. Some have actively blocked attempts to allow independent investigators to assess the situation in Xinjiang. All three of the people I spoke with agree that economic ties to China play a major role in a country’s response to the internment camps. China is the second largest economy in the world and has made significant contributions to economic development in other parts of the globe. Referring to the Belt and Road Initiative, Byler notes that the construction of physical and digital infrastructure subsidized by China forces many states into a difficult position. “I think many leaders are trying to balance those economic concerns with the feeling that they need to also stand up for human rights for their Muslim brothers.”

For many of those countries, speaking out may also draw unwanted attention to domestic circumstances, Byler said. “We also have to understand that a lot of Muslim majority nations are not democracies, that there are human rights abuses happening in those states as well.”

China’s power also presents a conundrum to its allied nations. In Turkey, for example, where there is a large Uyghur expat community, there is tension over a pending extradition deal with China. China’ demands for the extradition of Uyghurs based in Turkey are perceived as a precondition for the delivery of Chinese-manufactured COVID-19 vaccines. These dilemmas extend to several other countries in the Middle East and South Asia. “In the case of Pakistan, China is an indispensable ally,” Kelemen said. “They are pushed into a position where they must abide by whatever China pleases, be it for economic or security reasons. What is worrying is the possibility that some countries might perceive this as a sort of blueprint for them to deal with similar issues in the future.”

Many Muslim-majority states are also suspicious of the United States, mainly due to the damages they suffered throughout the War on Terror. Byler said that for some countries, Chinese support is essential. “There’s a tension there between the US and China, where many nations want to have a counterweight to the power of the United States. And they see China providing that for them”.

It should be noted that the actions of state governments do not necessarily reflect the will of their citizens. In some places, including Malaysia, Indonesia, Bangladesh and even Palestine, citizens have expressed a great deal of solidarity with the Muslim people in China and want to see their states to act more aggressively in their defense. Byler hopes that as coalitions build around the situation in Xinjiang, there will be more potential for change. “There have been street protests to that effect. In Palestine, around 80% of the population agrees that these camps are a crime against humanity, and that China is oppressing its Uyghur minority. They believe the media reports. I think we shouldn’t regard the positions that Muslim leaders are taking on this issue as normative for the Muslim world.”

In other Muslim-majority countries, engagement with the Uyghur issue is limited, mainly due to a lack of civic awareness or because the government does not allow for much activism work or transparency. “This is an obstacle for a lot of people that are aware, to continue to do efficient work to address complicity and the genocide of these Muslim brothers and sisters,” Millsap said.

Taking a Stand

How might average citizens with limited outlets for political participation take a stand against the human rights abuses perpetrated against Uyghurs? According to Millsap, raising awareness is one of the easiest and most direct methods of participating in advocacy for Uyghurs, including through social media platforms. There is a host of online resources, such as the Campaign for Uyghurs website, that provide detailed information about the situation in Xinjiang. Engaging oneself politically from home is also an option. “Raising your voice to your elected officials is fairly straightforward,” Millsap said. “It doesn’t have to be very elaborate. Just sending a letter or making a phone call to say you’re concerned about the issue goes a long way.”

Consumer pressure ought to be widely applied in order to discourage global brands from profiting off of Uyghur slavery, Millsap said. “Consumers need to come forward and say, ‘I don’t want any part of purchasing products that are manufactured in this manner.’ And this has been brought into the limelight more recently, as we see how China has chosen to retaliate against brands that have put up statements about how they are concerned with the issue of forced labor.”

Kelemen agrees. “My personal view is that in order really undermine what is going on, private businesses and supply chains specifically must be targeted.”

Moving Forward

I asked all three for their projections for Xinjiang in the coming five to ten years.

Kelemen believes that the camps will ultimately fail in erasing an entire ethnocultural identity and may even have long-term unintended consequences. “What this can do in the long term is to actually increase any kind of grievances that exist towards China from the Uyghur community.”

Millsap is concerned about the long-term implications of internment in the re-education camps, including generational trauma as well as irreversible damage to the Uyghur collective imagination and individual members of the community. Realistically, she says, this is the last chance for the international community to recognize that the Chinese Communist Party will never reform. “The hope right now for the five-year projection is that things continue as they have in terms of the international community awakening and taking action to address the threat that the Chinese regime poses to the entire globe. The ultimate optimist viewpoint would be that eventually the Chinese people themselves will wake up and be done with the CCP. But I think that that is more like a ten-year goal.”

Echoing Millsap’s affirmations, Byler expressed hopes that the Chinese population would eventually stand up against the abuses of the Chinese government against Uyghurs. “I think a real key to changing the situation is for the general public in China to really begin to shift their view on what’s happening there, to begin to push back against the government narrative, to begin to see through sort of the Islamophobic rhetoric around terrorism, and to understand the costs, the moral costs, and the kinds of legitimacy problems that the Chinese government will encounter.” This would begin with the Chinese diaspora population, who live abroad and have access to non-Chinese and non-state media. It will be more difficult to communicate these realities to people with highly controlled and sanitized news sources, but Byler maintains that the evidence is overwhelming. “I think a camp system is really hard to hide. Colonization is really hard to hide.”

Millsap agrees with Byler that boycotting the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics would send a powerful message. There is some evidence to suggest that the Chinese state does respond to public sentiment, if only in a delayed manner. “It may be hard to see, but putting that pressure on them, letting them know that the eyes of the world are on them, keeps them from perhaps engaging in even worse behaviors,” Millsap said.

Kelemen is hopeful that continued international pressure and the withdrawal of international investments will provide incentive for the Chinese government to at the very least downsize their internment operations. Similarly, Millsap sees diplomatic and economic pressures as ways to move forward. “We can continue to apply sanctions and continue to employ economic methods. That’s the only language the CCP speaks; they don’t have a moral bottom line. If you’re expecting them to act as a rational actor, historically, that’s never happened. In this instance, only money works. So we have to keep speaking the language they understand.”

Donald Johnson

One of the sadist stories in the world.