I’m a young Canadian who wants to know what the world will look like in 20 years. I want to know the challenges I will face. And I want to know about the major issues in the world today, so I can imagine a better tomorrow.

As naturally curious and self-aware beings, humans have often questioned the future, and have been skeptical about its promise. Shortly after the horrific First World War, Yeats described the apocalypse he felt was close at hand in his poem “The Second Coming”: “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold; mere anarchy is loosed upon the world. The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere the ceremony of innocence is drowned.”

Today, there is also a lot to be concerned about. The world is experiencing multiple global crises — a severe economic downturn, persistent global poverty, climate change, war and conflict, and resource depletion. It’s difficult not to be discouraged.

But I want to know where the world is failing and where it is succeeding in dealing with these crises. What are the biggest challenges facing our world? What role will Canada play in resolving them? And where is there hope?

I spoke with four prominent Canadians with diverse expertise and asked them. The Honourable Paul Martin, CBC television and radio host George Stroumboulopoulos, economist William Watson, and Green Party leader Elizabeth May graciously shared their views on today’s most pressing global issues.

The financial crisis

What are the implications of the financial crisis for the poorest on the planet? How do you see Canada and the international community responding effectively in terms of aid, trade and other forms of support? Will it be enough?

There are many people, given that this financial crisis finds its roots in the banking systems in Europe and the United States, who felt that it really would have little or no effect on the developing world. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Major sources of income in many developing countries are remittances from immigrants from the developing world, now working in Europe or the United States and Canada. Those remittances have declined substantially because the first people hit when people lose their jobs in North America and Europe are immigrants. So all of a sudden their major source of money has dried up.

Foreign direct investment has also dried up substantially as companies that are in trouble within the US and Europe have to pull in their horns all of a sudden. And the first place they pull them in is with investments that are made in the third world. Then you have the basic commodities that are produced by a lot of these countries disappearing, mining as an example. So a lot of the industries that were employing people in the third world are gone.

And what is perhaps the most tragic of all, rich countries started spending money in huge stimulus packages and not a penny went to the third world.

I am very actively involved with Africa, which did get a hearing at the London G20 meeting but it wasn’t followed up.

The fact of the matter is that in the part of the world where the people are the most vulnerable and suffer most from this financial crisis, they found their balance sheets and income statements devastated. And as the developed world brought in massive stimulus packages to help their own economy, they simply forgot about the third world.

What can be done about this? You’re involved with the African Development Bank, what role do you see it playing?

Fortunately, multilateral development banks such as the African Development Bank, which I work with, have been providing some extra capital to deal with the poverty issue. It’s by no means sufficient.

I believe that the developing world has got to be given a hearing at the G20 meetings, which are going to be held in Canada in early summer. We’ve also got to recognize that this recession has hit them harder than anybody else, and that they’re going to require a huge investment. I’d like to see a lot of that investment take place in agriculture, and not in the land grabs that we’ve been hearing about. Rather I’d like to see investment in the improvement of the agricultural base of these countries. We’ve already come through one food security crisis and I believe there is another one on the horizon.

When wealthy countries look at their budgets and their economies during a recession, they make cutbacks. And one of the first things that gets cut is aid to other countries. Another challenge is that when an economy comes out of a recession, and spending starts to be explored, it takes longer for aid to restart. Even aid on an individual level, it takes longer for donations to begin again. People look at their economic situation and think “we can’t afford to give this money,” whether it’s true or otherwise. Canada has positioned itself quite nicely with regulations and such to prevent the collapse of the banking system. In terms of recession it wasn’t hit that badly. The auto industry was in the news though, because it is obviously important to Canada and certainly Ontario. It was a hard reality dealing with that part of it.

Do you think aid is the best way to help the poorest? How else can the poverty issue be approached?

It’s a complicated question because every situation is different, but aid is important and it may be necessary to get the ball rolling. In terms of whether the recession is an opportunity to decide if aid is the most effective way to help the poor, sure it’s an opportunity, but an opportunity isn’t anything more than just that. It’s an opening. How you fill that opening and what you do with that opportunity is what’s important. Unfortunately, a lot of the people making the decisions at this moment of opportunity are the same ones we had during previous periods of opportunity, and we’re still in the same boat. So I don’t know how much is likely to change.

It’s not quite true that financial crises are exclusively a rich-country affliction but I suspect that in fact the very poorest on the planet haven’t been much affected by the economic downturn that has so preoccupied the rest of us for the last 18 months. The very poorest are that way mainly because, almost by definition, they aren’t connected to the world economy. If they were connected, they wouldn’t be quite so poor. “When you ain’t got nothing,” as the song goes, “you ain’t got nothing to lose.”

The very poorest don’t have quite nothing, but they don’t have much. What they do have, if they’re subsistence farmers, as many probably are, they may be subject more to weather cycles than business cycles.

As for aid, there’s been a response, though it’s hard to judge how big or effective. More invariably it is promised rather than delivered. The new view of aid is that it’s not all that effective even in normal times. Those who are hardest hit by the recession are probably several tens of millions of people in China and India and other newly-industrialized countries who have moved off the farm and into manufacturing in recent years, and are now being hit by the downturn. The most effective aid they can receive is probably going to come from the beginning of the expansion of social insurance in those countries. I doubt foreign aid is going to make much of a difference there.

For the longer run, of course, having China, India and the others have substantial middle classes and sufficient wherewithal to provide basic protections for citizens is a very good place for the world to go.

The financial crisis is very much linked to the climate crisis. The situation for the poor is at least doubly bad because of the implications of the finance crisis, and the implications of the climate crisis. Some nations are recognizing that the climate lens is essential in understanding effective responses to the financial crisis and global poverty. That kind of response focuses on a domestic stimulus package, which shifts the nation to greater reliance on renewable and efficient energy. These nations also understand that the next phase of climate negotiations must include a substantial transfer of funds to developing countries for the climate crisis adaptation agenda.

For instance, Bangladesh is already working with advice from the World Bank and notable scientists on how to figure out how to relocate the 40 million people in southern Bangladesh close to sea level to the northern part, which severely lacks infrastructure. The development crisis, the climate crisis and the poverty crisis are closely interlinked.

So far the international community has not responded effectively to any of these crises.

Reactions to the financial crisis have been predictably focused on how industrialized nations can rebuild their economies quickly. Recovering the global economy, in theory, makes it possible to imagine improving the situation for the poorest. But just as the climate crisis is not of the making of the poorest of the world, neither was the financial crisis in terms of its making. It’s the wealthiest of the wealthy who, through greed and lack of regulation, spun the financial world out of control and let it come crashing down around our ears. There is not nearly enough in place to prevent this from happening again.

Rebuilding the system as it was is a threat to the poor and capitalism as well. The only real threat to capitalism on this planet is a capitalist system that fails to constrain the greediest. In any steady state economy, which is what Greens favour, you need to recognize the necessity of full employment and a healthy society. And your chances of doing that go way up when you don’t have an unregulated capitalist system that is built on the false notion that there are no limits to the global ecosystem.

This is a threat to capitalism itself. I think the September crisis makes that clear.

So with respect to the poorest of the poor, a fundamental change in the architecture of the economic financial system will help them, and it will protect wealthier nations as well. What we are currently rebuilding, however, is a global economic system that is not sufficiently different from the last one. If we don’t talk about greater regulation over financial markets, and we don’t ensure that banks are not buying and trading in paper without proper evaluation of the content and risk factors, it will negatively affect the poor and the taxpayers who will end up paying for a bailout. The time of bailing out is over; the time for regulating much more closely is long overdue.

Climate change

What are the greatest risks associated with climate change? And how do you see them being overcome?

The greatest risk is to the most vulnerable in the third world. So many third world countries are low laying countries on coasts, like Bangladesh or the Maldives, and face the threat of catastrophic flooding. The risk of drought in Africa is also overwhelming. We’re already seeing that climate change has had a direct negative impact on their agricultural sector and their sources of water and food.

In addition, if the greatest risk is to the most vulnerable in the third world, an even greater risk is to young people. The youngest and fastest growing population in the world is in the third world, and Africa in particular. Thus the risk of climate change is not only to the vulnerable now, but to the vulnerable among future generations.

Do you feel the Canadian government made any positive changes in regards to environmental damage? What changes do you think still need to made?

There is a lot of ground to be covered. Canada’s lack of leadership and almost lack of interest is simply incomprehensible. In the lead up to Copenhagen some were even asking the United States to put pressure on Canada so we would take up our responsibilities. I can’t believe that; it’s beyond the pale.

We can no longer explain the climate issue as an environmental issue, because it’s now the largest security threat facing the planet. Climate change is an environmental issue to the extent that drowning is a water issue. We’re now looking at whether civilization can survive the decisions our generation has made and that we are still making. The situation is at the moment desperately dangerous.

We have lost all the time that was available for delay, denial and procrastination. I’ve been working on climate issues since 1986 and I have not said with great frequency “it’s almost too late”. I’m a very positive and upbeat person by nature, but you can’t negotiate with the atmosphere; it really doesn’t give a damn about humanity.

So this is not about protecting the environment. It’s fundamentally about whether we as a civilization, as a species, will maintain anything like an acceptable quality of life.

Scientists say we have already changed the chemistry of the atmosphere, and now have over 30% more greenhouse gases in our atmosphere than at any time in the last billion years.

Some climate change deniers like to point out that there was more CO2 on the planet billions of years ago, and that’s fine, but that was the age of the reptiles. Humanity has never developed in an atmosphere with levels of CO2 as high as we have now.

We’re adding two parts per million per year to the CO2 levels globally, and we’re at about 386 parts per million closing in on 390. Between 400 and 420 parts per million, we will start to lock in some environmental impacts felt worldwide, involving a global average temperature increase reaching 2 degrees Celsius above the levels of temperature that we had before the industrial revolution. If we go to 3 degrees above the global average temperature change, which on the trajectory of business as usual is an inevitable change that will take place very soon, it locks you into runaway global warming.

We must avoid runaway global warming because that is the scenario in which you can’t imagine how any civilization or country, let alone the poor, could begin to cope with, say, a significant sea level rise or with persistent drought in areas of the world that grow food.

The impact on human societies will be simply unbearable. Systems will crack and fall apart globally. And we don’t have a single nation on earth currently advocating what needs to be done.

Canada is not going to acknowledge the risks of climate change so long as Stephen Harper is Prime Minister. He has made it clear that the Kyoto protocol and action on climate change through the UN are things he wants to avoid.

We were the only country on earth that repudiated the signed and ratified Kyoto Protocol. Our record on this issue can be easily condemned for making promises and not meeting them, and the previous Liberal government can be charged with making lip service, but at least there was some effort to try and reduce greenhouse gases in the plan the Liberals put forward.

Undermining the Kyoto protocol has been the exclusive purview of Harper.

Canada’s role is to be global saboteur. It’s not that we’re not keeping up with the others, but we’re aggressively working to block progress with other countries we consider like minded, which these days includes Saudi Arabia and smaller members of the former USSR that want to do nothing. We are arguing against many hard targets, and arguing that our role in international relations is to defend the tar sands and not future generations. The most we can hope for from Canada, as long as Stephen Harper is still Prime Minister, is that no one in the world is going to be like Canada.

The major danger I see environmentally is that people are not facing up to the true trade-offs involved in many of the policies recommended by eco-ascetics in the rich countries. The idea that there is no trade-off between the environment and the economy is just bunk. We can’t all be environmental engineers. Somebody still has to produce stuff. And I don’t think two or three billion of the poorer earthlings are going to buy the argument that economic growth is over and they now have to accept a lower material standard of living than most people in the OECD countries have come to take for granted.

I also don’t believe people in the OECD are going to volunteer for substantial changes in their way of life. My family and I are doing our best to give up plastic bags, but that kind of piddling superficial change is about the only kind that can get through democratic political systems. Much more than is yet appreciated, we’re going to need a technological fix to our environmental problems.

I obviously could be completely wrong—wait 50 years and the world can be shockingly different from what you expected—but I don’t believe most people will accept a permanent sentence of poverty. The trouble that rich-country politicians are having in getting their electorates to accept a big increase in the price of carbon is the best evidence of that. Most economists would argue that you’re not going to get a big decline in consumption without a walloping increase in price. And it just isn’t happening.

Everything is connected, so you affect one thing you’ll affect another thing. You affect the natural habitat of a certain animal that has a role in the ecosystem, as all do, that ultimately affects everything else. Climate change isn’t just one issue it’s a collection of problems. From your food sources, to your personal health, to the stability of the ecosystem – they’re all affected by climate change.

Another problem is that people make it a political issue instead of a health and well-being issue. If it were about health and well-being, we wouldn’t look at it in terms of opportunities and backlashes and things like that.

Really, it’s about sustainability, and trying to make a difference wherever you can. I don’t have a lawn that I have to water. All my plants are indigenous, so they’re built to grow there. And I have living garden as a roof so the rain that goes in there irrigates and gets recycled. We just need to try to make the smallest environmental footprint we can.

War, conflict and terrorism

With many Western nations involved with the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, the threat of terrorism, and increasing concern surrounding nuclear arms proliferation, especially in Iran. What role do you see Canada playing in regards to global conflicts and warfare?

Millions of the world’s most activist citizens regard Dick Cheney as a kind of Darth Vader character, except less warm-and-cuddly. But as I read his two terms as vice-president he was preoccupied with one big job: preventing a nuclear or biological 9/11.

His view that a nuclear device or a “dirty” conventional device going off in one of the world’s major cities—he probably was most fixated on its not being an American city—would be a horror many times worse than 9/11 seems to me to be essentially right. It’s an inconvenient truth. It may be unpleasant to think about. It’s certainly annoying to have to spend resources preventing it, but it’s clearly something that has to be worried about. How you prevent it from happening is debatable. Maybe intervention in Iraq made it more likely rather than less. That’s a big if-question to which I don’t think there’s a conclusive answer.

I don’t see NATO involvement in Afghanistan as being inconsistent with prevention. In fact, the official rationale for it is that failed states are breeding grounds for mega-terrorism and that Afghanistan was a breeding-ground for 9/11, which it was.

Are there other ways to deal with the threat apart from war and policing? How do you persuade Islamic extremists to be less extreme? Injustice and intolerance are not excuses for mass murder, but I think you do have to address your own role in any obvious injustices and you also make clear that your own societies are pluralist and tolerant.

Beyond that, you don’t compromise your own principles, which for most of us are the classically liberal ones of liberty, including liberty for women, and tolerance. We have to make clear we will not tolerate intolerance. If those values are under attack, and they are, we have to defend them. No doubt it will require sacrifice. Our societies have made considerable sacrifices before. It is not beyond us to do so again.

I think in regards to nuclear proliferation, whether it is in regards to North Korea, Iran or any other country, I think Canada’s voice has got to be heard, and heard very strongly. But I also believe that there are areas where Canada can play a particular leadership role.

In terms of terrorism, people will point out that many of the terrorists are middle class, and they use that as a reason to say that a terrorist does not have roots in poverty, but it does have roots in poverty.

I think that in places like Africa there is a tremendous leadership role Canada could play in anticipating and dealing with the poverty and thus terrorism. In the year 2030 Africa will have a population larger than China or India. In the year 2050 Africa will have the largest population in the world and the youngest population in the world. That population is either going to provide the world at that time the kind of growth potential that China is not presenting to the world. Or it’s going to be a source of huge insecurity in the world. There are no walls that are going to prevent those waves of migration coming out.

My belief is that Canada’s voice should be very much heard in the great debates of today. But we should be taking a leadership role in many of these areas where countries like the US are unable to do so.

In terms of the poverty that exists, the refugee camps that exist, and the lack of military security that exists throughout Africa: there is no doubt Canada could be a leader. The Africans would welcome us with open arms if we took a leadership role.

NGO work is one way to do it. Climate change is going to be a big source of insecurity and one of our basic goals should be to fund NGOs. Put the money in the hands of NGOs because it’s the NGOs that create jobs and will work to reckon with those communities, those small villages throughout Africa. That’s where the answers are.

The recession took all of the attention off the idea of stopping wars. The economy became the front page of all the news, because each country has its own set of circumstances they have to deal with. As for Iraq and Afghanistan, it’s a tough situation to face for the countries involved in the war. Much of the developing world is also having a really tough time though. With all the attention focused on Iraq and Afghanistan and the drama involving Iran, the others seemed to get left behind. The major conflicts are getting a lot of attention, and a lot of it is deserved, but we just can’t give them the only attention.

The Green party’s position is that we must become even more nimble globally. We are now one of the least engaged nations on earth in terms of UN peace keeping. And the conflict in Afghanistan is not something we’ll resolve at all with the NATO strategy.

The Greens’ view is that we should not be involved in a NATO mission, and we should only be in Afghanistan in a UN peacekeeping role. Canada and all the nations on earth need to be far more engaged through UN peacekeeping, along with diffusing conflicts before they escalate.

In June of 2008 the UN asked Canada to send four people to the Republic of the Congo to assist, and we refused because we apparently didn’t have four people to spare. This is something Canadians don’t recognize. We’re living with somewhat of a myth that we’re environmentally responsible and peacemakers.

It is disconcerting that Stephen Harper didn’t attend key climate talks at the UN, but also that he didn’t show up for the disarmament talks either. Many ask what Canada has to do with disarmament. Well we weakened the nuclear non-proliferation treaty when we decided to trade in nuclear technology with India after India violated the treaty and built its nuclear bomb using Canadian technology.

This is not a small matter for Canada. There has been a shift from a country that is responsible on climate and nuclear arms proliferation to one that decides neither of those issues really matter so as long as we can sell nuclear technology. Canada is actually undermining nuclear security and ecological stability and that’s not something the Canadian public really knows we’re doing. Our commercial mainstream news media is so brain dead that nobody hears about Canada’s position on these international issues.

Food, water and energy needs

With population growth, food and water scarcity and energy resource depletion around the world, what role do you think Canada will play in addressing the world’s resource shortages? Will any of these issues have a particularly large impact on Canada?

Canada will obviously be affected by water shortages, but we will be affected indirectly compared to places with major water shortages in the world, like Africa. In terms of energy resources, there need be no shortages of energy resources. The technological capacity for renewable energy is huge, and Canada should be leading that field. For instance, there is a group that’s looking at building a huge solar panelled field in the Sahara Desert that would be able to provide a substantial amount of electrical energy to Europe. As long as they work closely with the countries in the Sahel, these are the kinds of technological opportunities and positive resource solutions that are being opened to us.

The problem is we’re not spending the money on developing those technologies. Of the whole stimulus package that was developed by the Canadian government, none of it went into the development of renewable energy. There’s a huge role that Canada could be playing. We are an energy rich country, but an energy rich country should use its energy base to develop renewable energies. Why are the Danes the leaders in wind power? Why isn’t Canada? These are the kinds of things we should be investing our money in.

I hope nations won’t deal with population growth. The right to reproduce, though widely abused, is probably the most basic of all human rights. Compulsory sterilization, limits on the number of children a couple can have, and similar authoritarian policies, are to my mind abhorrent. I expect that, following the pattern of recent centuries, as poor countries become rich—and they will if their governments encourage competitive capitalism and open markets—birth rates will continue to fall. Perhaps it’s a poor reflection on us all, but when people don’t need children in order to fund their old age that seems to reduce the number of children they want.

I’m not sure there is a long-run food crisis. Misguided but trendy environmental policies drove up the price of corn and other biofuels in the run-up to the crash, but it’s not obvious that if artificial demands from the rich countries were removed from the market, there would still be a problem. As we economists would put it, the supply of nutrients is probably pretty price-elastic in the long run—that is, if price goes up more supply will be forthcoming—so that prices will not rise without limit. It goes without saying—or should—that we will best husband resources if we put a price on them. We say we value water but in most of our cities there is little if any connection between how much a person uses, and how much he or she must pay for it. (Except, of course, in the increasingly maligned market for bottled water.)

What role will Canada play? I suspect, that as usual, we’ll talk above our weight. As a country that has a lot of resources, we’ll probably continue to supply them. The trend of commodity prices has been pretty flat over the last 150 years, but if over the next few decades these prices rise steadily, our incomes will rise steadily, too. From those to whom much is given, much is required. As our wealth increases, so does our obligation to those with a less generous birthright. But I hope the 20th-century Canadian assumption that our governments can only fulfil these obligations will lapse. Hiring bureaucrats to do your compassion for you is actually not very compassionate, and not only because they may not be very good at it. As a country, Canada is a shining example (on a snow pile?) of the benefits to be had from open capital, goods and labour markets. I hope we will stand strongly behind those concepts in the years ahead—though I fear we won’t.

Having a lot of natural resources, Canada will be fine. We’re only as vulnerable to American corporations to the degree we allow ourselves to be. If America, Canada and Mexico can all agree on the terms of NAFTA and live by them, we just have to live out the reality we’ve created.

There is no single way Canadians can help resolve major world issues; there is a multitude of ways. Some should take the political route. There is no age barrier to getting involved in public life.

Others clearly should take the NGO route. When I was the Minister of Finance, I was a governor of the World Bank, and I never went to a WB or IMF meeting without meeting with the NGOs that were involved in development, never once. They can have a huge influence on government. Both in terms of dealing with government, because they develop a perspective the government can’t have, or in mobilizing public opinion.

There are institutions around the world that are looking for young people who basically want to dedicate themselves to public service. You can do that nationally or you can do that internationally. You can do it through government or you can do it through NGOs.

One thing that I think is very important is the third world at home. The fastest growing segment of the population is First Nations, Métis and Inuit. And I am very actively involved in the whole question of the future of aboriginal Canadians. I would simply point out that when I’m in Africa I see Canadians all over the place, and it’s a wonderful thing to see, but when I’m working here on a reserve or with the First Nations, I don’t see very many young Canadians.

I challenge people to get involved in the aboriginal field. I think that the single most important issue that young Canadians can face is the fact that so many other young Canadians are discriminated against and living lives that are in many ways a tragedy. Why is it that one of the greatest causes of death amongst young aboriginal Canadians is suicide? What kind of society are we building when we allow that to happen?

Stephen Harper isn’t interested in Canada’s “resources” plural. We have tremendous resource potential in wind and tidal energy, plus we have a lot of potential in solar. But the only resource that Stephen Harper is interested in is the Athabasca tar sands, and his personal pledge that Canada will expand production to 5 million barrels of oil a day. We are currently producing 1.2 million barrels of oil a day, so Stephen Harper’s goal is to see that expand almost five fold.

The only climate action – and it’s not really action – has been to revert money that was meant for wind energy to establish carbon capture and storage. This may have some long-term benefits that reduce harm to the atmosphere, but it is overall one of the most expensive, least useful things one can do, especially when our society is so wasteful of energy.

Our top goal should be to cut energy waste is half in Canada. That is the most practical and doable, plus all the technology is already available. But the pricing continues to tell companies it’s cheaper to waste energy than conserve it.

And the focus on the tar sands means that we can’t create jobs in other sectors. The high volume of oil exports drives up the Canadian dollar, causing the loss of hundreds of thousands of jobs in manufacturing and pulp and paper and other sectors.

What do we do about resource shortages globally? Well, Canada is not particularly looking at anything other than the myth of endless growth. Harper remains clearly committed to the expansion of the tar sands, and it’s plain that he opposes anything that represents a significant transfer of wealth from North to South. He has already described Kyoto as a socialist plot.

Global population pressures, lack of water, and burgeoning environmental refugees into the billions of people are just not on his radar screen, because he doesn’t believe the issue is real. However, significant resource depletion means we are no longer talking about a simple increase in immigration. The planet could be dealing with millions of people clamouring for resources, for food, water, for survival within a decade or two. That is likely to be so disruptive to geopolitical security that it wont just be a change in our culture, it will be cataclysmic. And that is not something anyone can adjust to.

The hope for Canada is that we’re a democracy. No one threatens to cut off our fingers or visits our homes and kills our family, like they do in Zimbabwe or Afghanistan.

We have no excuse for our widespread laziness around civic engagement. I’m not saying the public is to blame and blame the victim, but it’s disgusted by the behaviour of politicians and reacts by not voting. Choosing not to vote though is actually giving a pat on the back to the most cynical kind of politics. Voting is part of our responsibility to better the world. The other part is to make sure that between elections citizens around the world are engaged and inspired with hope for the future.

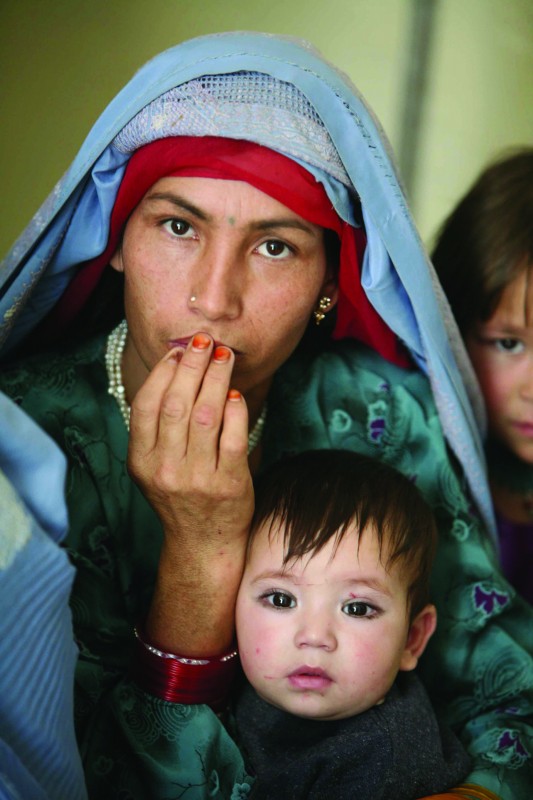

Photo: Julius Mwenu/IRIN

As soon as people wake up and say “I’m not prepared to tell my children, to their faces, that I didn’t do anything to make sure they had a liveable planet,” transnational corporations, supine media, and politicians who don’t think about the next generation wont be able to carry on with a business as usual agenda.

The deliberate effort over the last couple of decades has been to redefine our role in society from citizen to consumer. We have to shake off the addictions of consumer culture that tell us we have no political clout. Why should a whole generation wonder about losing its future? We absolutely do have the ability to turn this around.

People have to show up at demonstrations around the world to show governments that it’s not acceptable to pretend that the climate issue isn’t the most important issue facing us, and that they absolutely have to accept hard targets.

The largest greenhouse gas emitters are big companies, and they don’t want to be controlled or constrained. So lets get over the idea that you cannot move forward on this until every Canadian has already spent every penny they have on energy efficiency, when all the pricing signals reward waste.

It’s not a question of Canadians not being ready, or not doing enough. It’s that polluters don’t want to be regulated. Individual Canadians have clout and power and need to find those political muscles and start using them. If we could shake ourselves out of apathy and defence of impetus, we absolutely have the tools we need to work our way through this.